Israel's Innovation Economy: Will the Miracle Last?

Widespread inflation globally and possible recession are significant pressures for the Israeli tech innovation ecosystem. On top of political challenges. Where does it lead?

Note from the editor, Vivian Bercovici: When serving as the Canadian Ambassador to Israel from 2014-16, the question I was asked most frequently by visiting delegations was: “How can we replicate the Israeli tech innovation success?”

My stock response was that they should start by reading the book Start Up Nation - which distills the key elements of Israel’s story into a great read and roadmap. Not surprisingly, as with so many things in life, I found that everyone was looking for a “quick fix”; the magic potion. Sadly, there isn’t one.

Many refer to Israel’s tech innovation economy as a “miracle”, but in truth it is much more the result of vision, focus, discipline, determination and an efficient collaboration between the private and public sectors. And, yes. A dash of brilliance.

I first approached Eugene Kandel to consider writing this piece in late spring, 2022, when State of Tel Aviv launched. His background speaks for itself. I had the good fortune to meet him when I was Ambassador and he was working as Head of the National Economic Council in the Office of the Prime Minister of Israel as well as the Economic Adviser to the Prime Minister.

Throughout his career as an academic economist, Eugene has also been engaged at the highest levels of government to provide pragmatic policy advice, particularly with respect to Israel’s tech innovation sector.

I could think of no one better to explain the arc of the development of the tech innovation sector in Israel.

These days, Eugene is the co-chairman of the Start Up Nation Policy Institute, working in close collaboration with SNPI CEO Uri Gabai, a friend and colleague of his for many years. Also an economist, Uri brings to his role decades of experience working in the public and private sectors with a particular emphasis on tech innovation.

Together, Eugene and Uri have written a succinct, fascinating overview of the development of the tech innovation sector in Israel over the last 50 years.

The economic miracle that many take for granted in Israel today was made possible, to a large degree, by the visionary and bold economic reforms undertaken by then Minister of Finance, Benjamin Netanyahu, in 2003-5. We dig into that issue here.

But things have changed, dramatically, in the last few months. And there is widespread concern that the political instability currently seizing Israel will cause significant, lasting harm to the economy and, specifically, the tech and innovation sector.

For more on the recent political and economic unrest in Israel, have a look at our site, stateoftelaviv.com. We have covered this issue extensively.

In addition to this essay, next week, we will drop a podcast interview with Eugene and Uri, in which we delve more deeply into some of the challenges facing the government and Israeli society today; challenges that were well understood months ago and are not at all related to present turmoil.

Sign up here and we will deliver the podcast straight to your mailbox. You don’t want to miss it.

It is such an honor to publish this essay. Eugene and Uri set out so clearly the major milestones that mark the gradual maturity of Israel’s innovation-based economy. Their perspective is invaluable and I know that this piece will be read carefully by policy makers, entrepreneurs, leaders in big tech, business operators and many others who would like to know how Israel made the desert bloom.

Metaphorically, of course, in this instance.

By Uri Gabai and Eugene Kandel

I. The Israeli Tech Miracle: How Did it Happen?

That Israel is recognized globally as a powerhouse of technological innovation and entrepreneurship is old news. We seem to take it for granted and almost assume that this new economic reality is a law of nature – some sort of permanent state.

Now and then we pause and marvel at this miracle that has transformed our economy from one that was agriculturally based and considered to be “emerging” – just a few decades ago - to one that is innovation based. In Israel, we have come to see this as being the “natural” outcome of certain key qualities of our national character and society, a combustion of sorts; involving the legendary Israeli “chutzpah”, mandatory army service where elite units develop new technologies and train young experts, and excellent academic institutions especially in math and computer sciences.

Fundamentally, though, the Israeli innovation miracle, is much more a story of vision, disciplined planning and execution, creating the conditions for the gradual evolution of an ecosystem. Step by step, the components needed to re-imagine this small country - far from any substantial market - into a global tech hub, were conceived, designed and implemented.

The development of the Israeli innovation-based economy was no accident.

It was the product of strategic leadership, smart policies and an effective partnership between industry and government. These are the core elements supporting a unique model of a market-driven innovation ecosystem based on R&D and entrepreneurship that is also well-connected to international tech companies and markets.

But our journey is ongoing. The next stage of Israeli innovation is upon us. In this phase, the focus must be on transforming Israel from a country with a successful tech industry to a nation and economy that integrate technology and innovation into all aspects of life. This will necessitate an increase in numerous factors: the flow and volume of growth and large tech companies; cultivation of leadership for the next decade; and integrating these technologies in health, education, transportation and every other aspect of civilian life.

As with the previous stages, this prospective reality will not transpire without intense planning. The proven approach of forming an effective partnership between government and the industry must be implemented again. Without this critical collaboration Israel could squander its technological prominence, and if that should come to pass, it would be near impossible to regain.

Global competition for cultivation of innovation hubs is intense. If an ecosystem does not constantly grow and evolve, it becomes obsolete in a matter of years. This is especially worrying since a certain complacency on the part of the Israeli government has set in recently. Coupled with political uncertainty and the current social unrest, this imperils the future and supremacy of the Israeli innovation ecosystem.

II. Stage One: Laying Foundations (1970-90)

It is difficult to pinpoint a precise date marking the “beginning” of the Israeli innovation ecosystem.

Some see the 1920s, when three key academic institutions were founded - Haifa’s Technion–Israel Institute of Technology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Volcani Agricultural Research Center - as the inception of the innovation culture. Others view the weapons embargo imposed upon Israel by French President Charles de Gaulle in 1967 as being the “game changing” catalyst which forced the country to develop sophisticated technological capabilities for military use.

We see the 1970s as the critical decade in which the modern Israeli innovation culture was seeded, by a combination of the establishment of critical institutions and leveraging of global connections.

In that decade, the epicenter of modern technology was beginning to form in the United States, making it critical for the Israeli tech industry to form strong links with the American ecosystem. In 1972, IBM opened an R&D center in Israel and Intel followed two years later. These initiatives were prompted in large part by the return of Israeli employees living abroad that the companies were keen to retain. To solidify the connection between the ecosystems, the Binational Industrial R&D foundation (BIRD) was founded by the American federal government in 1977, with the mandate to facilitate US-Israeli tech collaboration.

But the 70s were also notable for the deterioration of Israel’s economy. In the decade following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Israel invested most of its resources – almost a third of its GDP - in a massive military buildup. This period has come to be known as the “lost decade” for the Israeli economy.

Overall government expenditure reached almost 70% of GDP in the beginning of the 1980s, and inflation skyrocketed to more than 400%. The crisis was deepening until the economic “package deal” of 1985 froze all financial and labor contracts – which led to a drastic reduction in inflation. At the same time significant market liberalization measures were introduced, which broadened the scope and scale of private sector initiatives.

In addition to the aggressive economic reform package, the government made another important and far-sighted decision in the mid 80s: to free-up resources for the private sector and direct them towards technology, and innovation. The 1985 R&D Law presented a bold vision for an innovative Israeli industry. Based on a strong R&D capability, the legislation also gave the Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS) the mandate and resources to actualize the plan.

III. Stage Two: Emergence (1990 – 1998)

Between 1990 and 1993 the OCS made its biggest impact by launching three seminal government programs to support the Israeli tech industry:

Yozma – meaning “initiative” in Hebrew – jump-started the VC industry in Israel. The Incubator program supported individual founders in developing their companies - financially and logistically. They were further assisted by the MAGNET consortia, which fostered collaboration between small start-ups and Israeli academia and industry.

These programs coincided and were enhanced by the massive wave of immigrants from the former USSR, many of whom were highly trained in science and engineering, creating a boon in talent for the emerging industry.

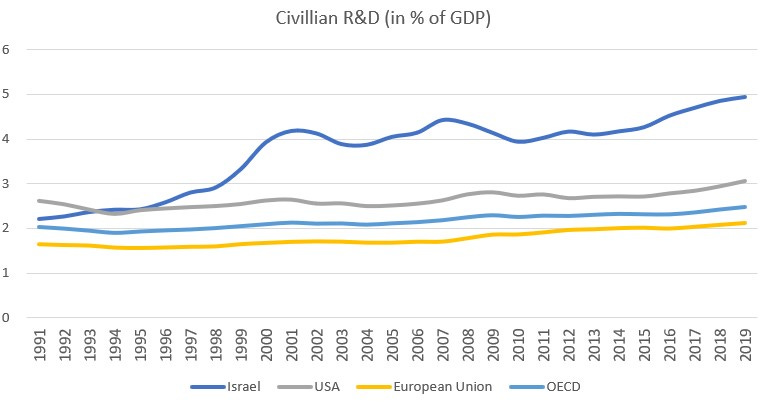

This combined potential met a dramatically expanding demand for ICT (Information and Communication Technology), in large part driven by the development of the Internet as a key technology. Israel doubled its investments in R&D as a percentage of GDP (see graph below) in less than a decade, growing much more rapidly than other developed economies.

Pioneering tech companies like Checkpoint and Tower were established in these years, and the Israeli ecosystem started to be recognized for superb R&D capabilities in the ICT space. But this recognition was limited and largely “below the radar”, even though almost 200 Israeli tech firms were listed on NASDAQ by the end of 1990s.

This all changed dramatically in 1998 with the first big “exit” of an Israeli company. Mirabilis – the Israeli start-up that developed the ICQ instant messaging software - sold for $407-million, causing quite a stir. The world took notice.

IV. Stage Three: Start-Up Nation (1998 – 2008)

If we had to pick a date – we would say that the Mirabilis exit marked the beginning of Israel’s ascendance as the “Start-Up Nation”. In the following decade, hundreds of Israeli entrepreneurs attempted to imitate that success. Many of them did succeed in forming successful start-ups that were later acquired by foreign tech companies.

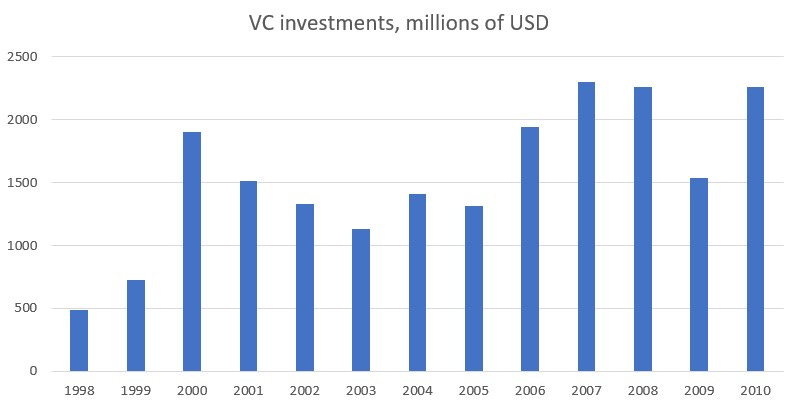

Venture Capital investments in the Israeli start-up ecosystem provided much of the financial backing needed to support this entrepreneurial culture. From negligible amounts in the beginning of the 1990s, VC investments grew quickly to exceed $2-billion (see graph, below). Most of the money originated outside of Israel (primarily the US) strengthening the emerging ecosystem’s linkage to global trends and international best practices.

During the same period, smaller companies encountered significant hurdles stemming from the extensive financial services regulatory reforms specified in the Sarbannes-Oxley legislation. Consequently, many Israeli tech companies were left without access to the critical growth capital they needed. This created an opening for major US tech companies, which had retained substantial portions of their profits offshore to reduce their tax burden. These industry giants began acquiring Israeli companies and establishing research and development centers in the country. Between 2000 and 2008, the number of these centers tripled, resulting in a growing number of job opportunities for technology professionals.

And with this development, the “exit” culture was established; many start-ups were established and built with a specific goal to sell them to a strategic partner. For more than a decade this was the main driver for many founders and investors.

Pundits declared this to be the natural course of events, claiming that Israel has a strong competitive advantage in creating start-ups and bringing them to an early stage, but no advantage whatsoever in growing them into large companies.

V. Stage Four: Tech Nation (2008 – 2019)

Publication in 2009 of the international best-selling book, “Start-Up Nation” sparked a new phase in the evolution of Israeli innovation. This event led to a dramatic and sudden global awareness of Israel’s vibrant innovation ecosystem, with two main effects:

It caused many world leaders to surmise that if Israel could create such an ecosystem, they could do it too. Almost immediately, this set off an intense and growing competition for ecosystems among countries and regions; and

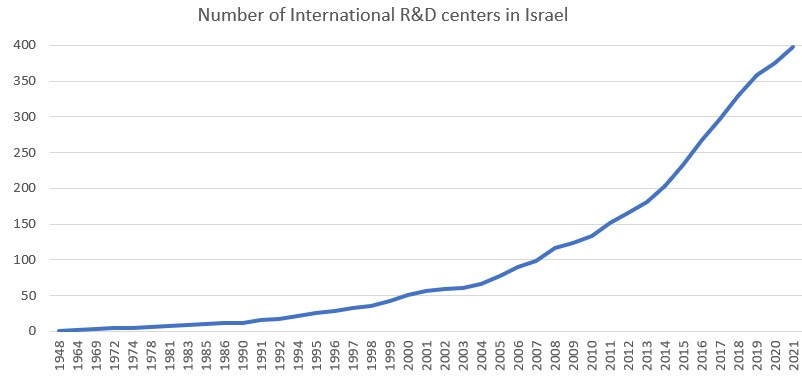

Secondly, dozens of multinational companies (MNCs) from all over the world also took note of the ecosystem potential and began to establish R&D centers in Israel, most often by acquiring local start-ups. In this decade, Israel became home to nearly 400 research and development (R&D) facilities, cementing its position as a leading player in the global tech sector (see graph, below).

The surge of global tech companies locating in Israel was an indication of its tech prowess. But at the same time, this positive development exacerbated one of the ecosystem’s most significant challenges: the shortage of qualified tech employees.

The massive influx of R&D centers drastically increased the already high demand for tech talent, which the academic institutions could not satisfy. This led to a chronic shortage of tech talent that we estimate to have grown from 12,000 in 2016 to more than 20,000 in 2021. As a result, tech salaries increased dramatically, negatively impacting the viability of Israeli tech companies that must compete for talent with behemoths such as Microsoft, Facebook, Google and Apple.

As a result, over time, the high-tech sector became less "Israeli" as an increasing proportion of tech talent went to work for non-Israeli companies.

This is the reality the Israeli ecosystem faces as it enters the fifth stage - the quest to become a scale-up nation. We believe this stage gained momentum in 2020, when the name of a well-known beer brand suddenly became associated with a global pandemic of catastrophic proportions.

VI. Stage Five: Scale-Up Nation (2020–?)

The beginning of this stage coincided with the maturation of the Israeli high-tech sector. As the Covid pandemic rapidly accelerated digitization, more mature Israeli tech companies thrived, raising ever-larger rounds of capital and producing unprecedented numbers of unicorns and public offerings.

The pandemic had a huge impact on the entire world and its economic shock waves are still reverberating globally. But it also accelerated the beginning of the much more “real” digital age. While much digitization was present in our lives before COVID, in spite of our smartphones and social networks, physical proximity was still extremely important and very much the norm. Those who could afford to do so lived in the center of large metropolitan areas. Those who could not spent hours commuting to and from the same centers. Job interviews, doctor visits, important meetings, commercial negotiations – many of these functions were still presumed to require one’s physical presence. Many people jumped on and off airplanes the way most use public transit or automobiles. Movement was constant. And despite e-commerce gaining momentum, most people still did their shopping in brick-and-mortar stores.

However, Covid-19 drastically altered this paradigm, upending long-held habits and attitudes and facilitating the penetration of innovative solutions that were feasible technologically but had not been accepted culturally before.

The lockdowns sparked a surge in e-commerce, while hybrid working solutions and online consultations with physicians became the norm. Logging onto Zoom calls replaced in-person meetings, and the resulting digital interactions were faster, safer, and more cost-effective than traditional methods. This mega-trend, which continues unabated, has fostered the development and adoption of more advanced technical solutions, particularly in data and software companies, further fueling growth in the tech sector.

Fortunately, the Israeli tech ecosystem was well-equipped to face this challenge. As most Israeli tech companies are software-based, they were well-positioned to capitalize on the surge in global demand. Numerous larger companies in sectors such as enterprise software, digital health, cyber, fintech and E-commerce - experienced explosive growth in this period.

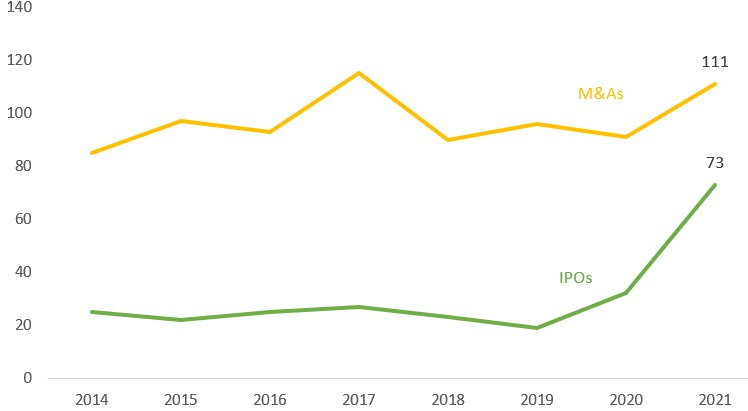

Unlike the “exit” culture decade, many founders of tech companies in more recent years have been focused on the creation Israeli legacy enterprises. The opportunity for these companies to shine came with the pandemic. 2021 marked a dramatic change in the acquisitions vs. IPOs trends (see chart below): 73 Israeli companies went public, mostly in New York, more than tripling the average of previous years. And while the number of acquisitions was still high, 2021 marks, in our opinion, a change in the long-term dominance of M&As over independent, large Israeli tech companies – public and private. Moreover, as demonstrated in a recent SNPI report, Israeli institutional investors that traditionally stayed away from investments in the local tech industry began to build expertise in recent years, and increased their investments in tech by 370%. In fact, the emergence of large Israeli tech companies led to an increase of almost 9,000% in the direct holdings of the Israeli institutions of their shares since 2016.

These trends are very important for Israeli hi-tech, as well as the country’s economy and society. As mentioned above, the Israeli tech sector is beset with an acute shortage of talent due the growing demand by the thriving tech industry. To remain competitive, Israel must keep growing and evolving its tech ecosystem, attracting more and more people to highly productive firms and professions.

Growing tech companies in Israel employ a diverse range of tech and non-tech professionals: designers, economists, lawyers, project managers, business developers, customer and investor support and more. This broader economic development must be the core element of the next phase of Israeli tech. In 2021 we saw a surge of non-tech employees joining the Israeli high-tech in ancillary roles. Demand for such employees more than doubled in 2021 – creating more opportunities for Israelis who are not going to be programmers and engineers to participate in the most exciting and rewarding sector in Israel.

Are we home free? Far from it.

The Israeli ecosystem is just entering this new phase, and it must still overcome several significant obstacles:

As the number of international R&D facilities grows, there will be a greater demand for highly skilled workers, exacerbating the chronic shortage in tech talent;

Many Israeli companies still feel compelled - once they reach a certain size - to move their headquarters and operational functions abroad for continued successful expansion. This perception is reinforced by foreign VCs, who often condition investments on such a move; and

It is becoming increasingly difficult for Israel's academic community, which is essential for the creation of cutting-edge technologies and the cultivation of new talent, to compete with other nations for the world's top professors. This is because of ill-structured compensation structure, which is unlikely to change.

In recent months, two new developments have emerged in tandem with these fundamental challenges. The risk of a global economic slowdown (triggered by high interest rates being implemented by central banks to combat inflation) is having a direct impact on the industry, as many Israeli firms are enmeshed with global markets.

As a result, companies are facing the hard reality that it may be easier to reach the “top” in the short term than to sustain success over the longer term. In order to demonstrate their resilience, they will need to maintain consistent performance through fluctuations of the business cycle. Only those that meet this test will emerge from this period stronger and more immune to future economic shocks.

The Israeli tech ecosystem, in particular, is facing another significant challenge - the current social unrest and political friction over the judicial reform, which is much more concerning than any global recession or fundamental challenge. Israeli tech leadership has been built on a wide-spectrum consensus that was stable across partisan divides and interests. Both left and right-wing governments recognized that this was the country’s only viable business plan, and Israelis took extreme pride in the country's high-tech achievements and the global recognition it gained.

Unfortunately, in recent months, this consensus has been destroyed.

For Israeli innovation to continue on its current, successful path, it is critical that this tension be resolved and the partnership between the tech ecosystem and the government be restored.

Only then will we be in a position to reinvent Israel’s innovation policy, aiming for one that is holistic, collaborative across the entire government, and strategic. The R&D-focused policy that worked so well in the previous phases is less relevant today. Instead, the focus should be on policies aimed at helping Israeli companies grow and remain in Israel, employing many more non-technical people for every technical professional. The Innovation Authority, as much as it tries, cannot succeed in this monumental challenge alone. This effort must be a part of a vision-driven government-wide collaboration, dealing with many different aspects relating to Israeli tech companies’ ability to become global leaders.