Fat Man, Thin Man: Will Netanyahu upend his economic legacy?

Some of PM Netanyahu's greatest achievements in office came as Finance Minister in the early 2000s. Is he willing to undo it all just to placate his far-right allies?

I.

While warming the opposition benches of the Knesset for the last year and a half, Benjamin Netanyahu used his time well. Among other diversions, he penned a quite fabulous autobiography, “My Story,” which was released several weeks ago in Hebrew and English.

Having had the privilege of seeing PM Netanyahu many times over the last decade or so, in everything from small, closed settings to huge convention halls, I can confirm that he is constant in his charm, charisma and intellect. A man with a giant brain and presence, he also has a knack for reading a room, whether it be cavernous or intimate. And he also clearly kept careful notes over the years.

Among his favorite anecdotes that I heard more than once over the years is his rendering of Mark Twain’s book Innocents Abroad, a chronicle of the author’s six-month tour across Europe and the Ottoman Empire in 1867. Twain was deeply unimpressed with the Holy Land, dismissing it as “desolate and unlovely.” He found beauty only in Jerusalem and commented on how sparsely populated the land was, and that those who lived here were, in his view, unpleasant in every way – in terms of character and aesthetics.

Netanyahu, I believe, referred to Twain’s book so often because it confirmed what many historians know to be factual: that before the Jews of Europe and Arab lands began to migrate to the area in large numbers, it was sparsely populated, and any economic activity and development was quite primitive. If Bibi said that he’d be accused of erasing Palestinian identity, or worse. If Twain says it, well, it’s less fun to attack.

In the years following Twain’s tour, waves of Jewish immigration made the desert bloom; a cliché borne of Zionist settlement and determination. Progress in the pre-state days required intense collective effort and resource allocation. Life was harsh and poverty extreme. Furthermore, so many early immigrants had brought along with them from Europe a predilection for socialism; a quite understandable political and economic response to the exploitation still rampant on the continent.

Those early socialist prototypes became state institutions and, over decades, ossified into a disastrous economic reality.

Fast forward to 1981, when I was living in Jerusalem, studying at the Hebrew University. These were the days of 120% inflation (and climbing), when I made the half-hour trip by bus into the center of town three times a week to exchange my dollars into local currency. If I withdrew my weekly budget in one go, within days the cash would be worthless.

Israel then was very much a poor, agrarian, emerging economy. Air conditioning was a rarity, meaning that businesses closed for daily afternoon siestas. The heat was withering and fans offered scant relief. Malls and high rises did not yet exist. Few people owned cars and those that did tended to have jalopies. Food was simple. Clothing was simple. Travel was something only the wealthy few could dream of.

It got worse before it got better. Much worse.

II.

By the time Netanyahu – in the midst of his first inter regnum from sitting as Prime Minister (1999-2009) – became Minister of Finance in 2003, Israel was on the brink of economic ruin.

A senior member of PM Ariel Sharon’s Likud-led coalition, Netanyahu was offered the political kiss of death – the finance portfolio. He understood this could well herald the end of his political career – as that portfolio often does – but he was fired up with vision and ambition.

As he writes in his book, Bibi cared deeply about the sclerotic economic institutions that tethered Israel to socialist inefficiencies. He took on the all-powerful Histadrut union organization, he challenged entrenched pension and other social service entitlements that threatened to bankrupt the country and he pioneered economic and tax incentive policies to stimulate an anemic private sector.

We tend to forget. The Histadrut not only choked any economic reform, but as the largest trade union organizer in the country was constantly leading one strike action or another. Planning and productivity were things that happened elsewhere. In fact, Bibi writes that in the 1990s, Israel boasted the record for per worker days on strike, outdoing even Italy, which was notorious for labor protests.

In Israel in 2003, government accounted for more than 50% of the GDP, pensions were on the verge of insolvency, welfare entitlements were massive and growing, and corporate and personal income tax rates were beyond punitive.

Netanyahu’s organizing metaphor for the chapter (which is, arguably, the most important in the book) and the Israeli economy is an anecdote he shares from his army days, which he regards as the core institution supporting national and social cohesion.

The “Fat Man, Thin Man” chapter chronicles his intense immersion in economic overhaul from 2003-2005 as Minister of Finance.

In order to right the listing economy, Bibi writes, vision, power (of the political kind) and will, were all essential. He brought game.

But his brilliance was in how he sold these measures – which were harsh – to the Israeli public. As he noted astutely, the social glue of Israel was army service; most citizens understood and accepted, without question, the importance of giving three years of their youth in defense of sovereignty and security. Bibi tapped into that shared experience by telling a story from his first day in basic military training, a rite of passage for all IDF recruits.

And he did this in a nationally televised news conference, which, particularly in those days, was a BIG DEAL, and is retold in his book:

The commander instructed all the fresh soldiers to line up in a row on a parade ground for the “elephant race.” (Of course, Bibi was first in line.)

“Netanyahu,” he said, “put the man to your right on your shoulders. Every other soldier do the same.”

I had to put a medium-sized soldier on my shoulders. To my right, a small soldier had one of the biggest men in the unit straddled on his shoulders, while a big soldier carried one of the smaller men on his back.

When the commander blew the whistle, I could barely move forward. The small soldier to my right collapsed after two steps. The big man shot off like a cannon and won the race.

All economies, I said (in his TV address), were engaged in a similar race. In each, the public sector, “the Fat Man,” straddles the shoulders of the private sector, “the Thin Man.” The private sector creates most of the added value in economies and is the engine of job creation and economic growth. It carries the public sector on its back and pays for it.”

In this very relatable anecdote, Netanyahu made the economic conundrum easy to understand and provided visuals, which often trigger memory and emotional responses in listeners. Israel’s economy was the thin man, collapsing under the weight of the fat man. The disproportionate welfare entitlements, burdensome taxes stifling entrepreneurship and innovation, and lack of competition, were playing out in day-to-day life just as they had on the parade ground of his youth.

III.

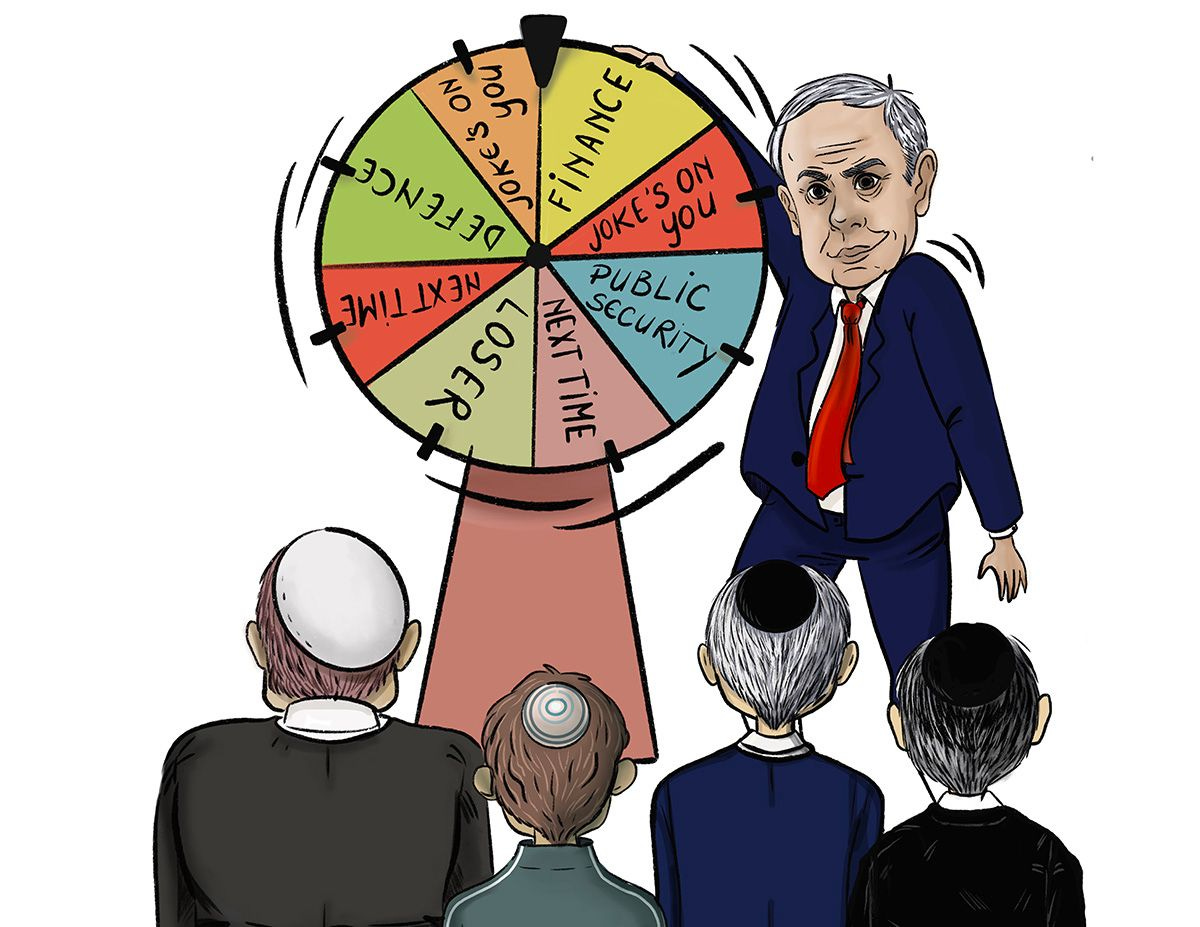

Dealing the cards in the post-election lobbying for cabinet portfolios is always an impossible task. But, this time Bibi is in a real squeeze.

Both Aryeh Deri – the head of the Shas party, and Bezalel Smotrich – who leads the Religious Zionism party – are openly vying for the top job in the Ministry of Finance.

Smotrich is the youngish, hardline leader of the Religious Zionism party. He has shown himself, over time, to be somewhat volatile in temperament and he has no formal training in finance or economics nor does he bring to the table any publicly demonstrated proficiency or interest in such matters. What he does do, however, is adhere doggedly to his platform supporting the aggressive and continued expansion of settlements in Judea and Samara, a costly enterprise – in hard cash and also economic and diplomatic arenas. His ascension to this critical cabinet post would turn heads – internationally and domestically – and not in a good way. His supporters credit him with having been an excellent Minister of Transportation from June 2019 for one year, demonstrating maturity and strong decision-making skills. Whatever he did there, however, is child’s play compared to the minefield of finance.

Smotrich is reputed to be a free-market kind of guy but he has said little, if anything, publicly on the matter, raising additional questions. Exactly what qualifies him for the job is a mystery. [1]

Aryeh Deri, the other most talked about possibility to head the Finance Ministry, leads the ultra-Orthodox Haredi Shas party, which commanded an eye-popping ten Knesset seats in Election #5 (up from 8 in Election #4). As with his United Torah Judaism Haredi Knesset colleagues, Deri has some stiff non-negotiable demands: full funding for religious institutions, including those in which adult men study full-time instead of working; and, a continued exclusion for all Haredi men from IDF service. The economic strain of these indulgences is significant and on a steep upward trajectory, as the Haredi proportion of the population is growing quickly. Without Haredi support Bibi would have no chance of forming a government.

Deri was also convicted of tax evasion in 1999 and served 22 months in prison. Once “rehabilitated,” following a legally enforced and long prohibition from engaging in political activity, Deri returned at the head of Shas. In January 2022 he dodged a second conviction on tax evasion charges by pleading to a lesser infraction and paying a fine. He was also meted a one-year suspended sentence by the court.

That a convicted felon, guilty of crimes of moral turpitude, and with a clear pattern of recidivism, should even be considered for the honor of serving in a position of such high trust is a giant red flag. It was difficult enough to understand public acceptance of his re-entry into public life, but the fact that his continued elevation raises few eyebrows is extremely disturbing. He will, at once, demand unsustainable economic largesse for his supporters and, in so doing, put enormous pressure on the Israeli economy.

One hears snatches of comments about Deri being on the “left” with respect to economic policy, but he doesn’t seem to regard his views as being important enough to share with the public. And then there’s the fact that he’s a stalwart member of the so-called “right-wing bloc,” which is total hokum. Nothing remotely right or left about the man. He’s all about religion.

IV.

The pool of working taxpayers who also serve in the army is diminishing at a disproportionately alarming rate. The thin man is becoming scrawny. And the fat man is morbidly obese.

If Benjamin Netanyahu makes either of these men – Deri or Smotrich – responsible for the nation’s treasury, he may well become the reverse engineer of his extraordinary accomplishments notched two decades ago.

The thin man will buckle under the oppressive weight of the fat man.

Or, put differently, the smaller and diminishing sector of economically productive Israelis will be unable and unwilling to bear the enormous tax burden that will be required to satisfy the demands of Bibi’s “right-wing” allies. Not to mention army service.

Tax rates will rise, incentive to produce will diminish, and the quite miraculous transformation of Israel from socialist to market economy could be undone. By the same man who built it.

On Sunday, President Isaac Herzog officially delegated to Netanyahu the honor of forming a governing coalition. Now, we wait.

And the thin man is very, very skittish about what’s coming.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please consider becoming a Premium Subscriber to State of Tel Aviv so you can access all premium content.

Editor's Notes

1) Smotrich is also pressing for the defense portfolio, which is even more surreal. Significant mystery attaches to Smotrich, particularly in the area of violence and defense. He was reportedly in custody of the Shin Bet police force in 2005 for several weeks on suspicion of planning a terror attack to protest the Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip. Smotrich has never denied such involvement nor promoted a counternarrative. Furthermore, his own IDF service was cut short from the obligatory three years but no explanation has ever been provided as to why. He also began his service at age 28, a decade older than is customary for Israeli men and women. On other issues, which were not explored in this article, Smotrich has distinguished himself as an exceptionally strong anti-gay leader who, among other controversial measures, supports conversion therapy. But, that is all for another day.