The Battle for Israel's Jewish Soul: Changing the Law of Return to Exclude Grandchildren

By Ksenia Svetlova

Note from the Editor, Vivian Bercovici: Ksenia Svetlova is a master storyteller who excels especially when exploring a topic so central in her own life: the experience of immigrants moving to Israel, in particular those coming from the Former Soviet Union. She spent her childhood in Moscow and moved to Israel with her mother as a young adolescent. Today, she brings a depth of understanding and compassion to her analysis of the impossibly complex issue of aliya – immigration to Israel.

Ksenia’s sharp analysis and strong political and social networks among the émigré community in Israel (Russian in particular) infuses her work with a unique intimacy and depth. Today, she takes on the issue of “who is a Jew”. And, who is Jewish enough to appease the gatekeepers.

These days, the gatekeepers in the newly formed coalition government with the power to make that call are hard-right orthodox Israelis, either in the ultra-orthodox haredi camp or messianic Religious Zionist parties. Ksenia does here what she does best: exposes the prejudices and turf wars that play out to the detriment of those wanting to make aliya and, ultimately, the State of Israel.

Israel will never lose the American Jewish community on issues of security and defense. Because at the end of the day, [even] if I disagree, this is existential. But when you begin to tamper with who I am as a Jew, what my right under Zionism is to return, you are dealing with my existential ‘being a Jew’.

Abe Foxman, the former director of the Anti-Defamation League, recently warning the Israeli government.

I. The Law of Return and the “Grandchild Clause”

Immediately following the November 1 election, when the Likud party began coalition negotiations with its future government partners, the term “grandchild clause” was suddenly bandied about. A lot.

This grabbed the attention of every person engaged in immigration to Israel (“aliyah”), and particularly the Jewish communities of the United States, Russia, Ukraine, and elsewhere.

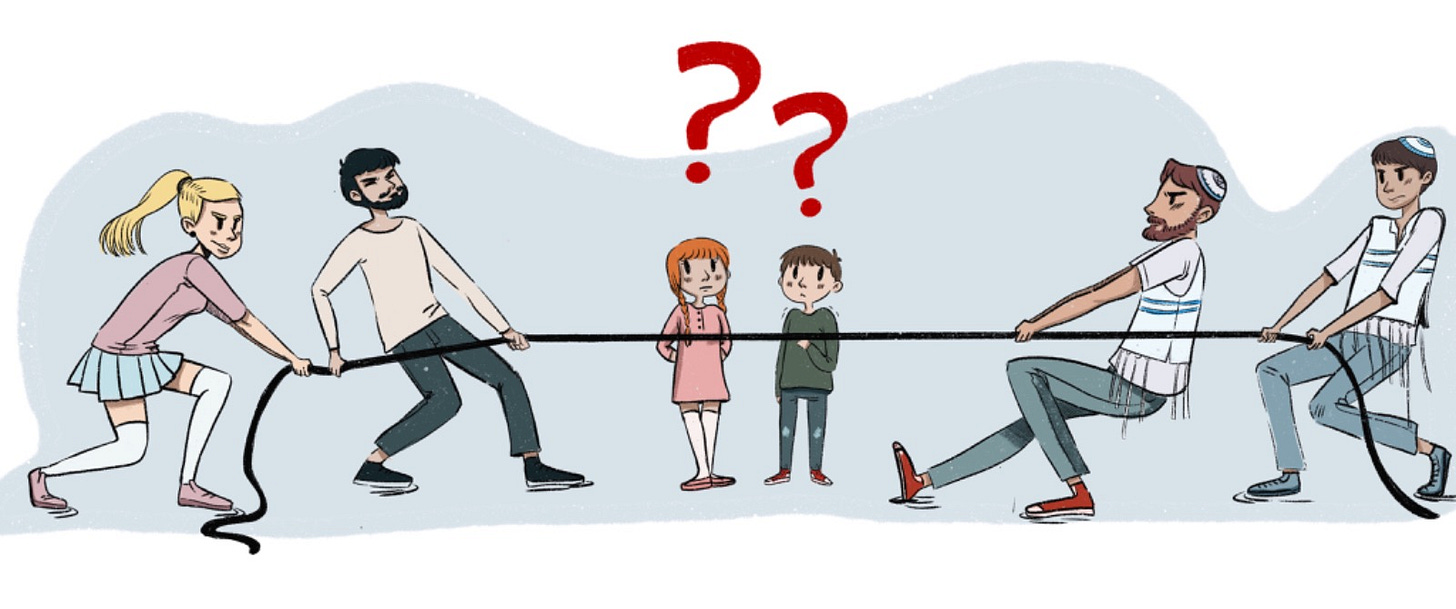

Bezalel Smotrich’s Religious Zionist Party wasted no time in tabling its demand to amend the Law of Return, which allows Jews, their children and grandchildren to immigrate to Israel. No questions asked.

Smotrich’s proposed amendment would exclude the grandchildren, revoking their right under Israeli law to make aliyah. In the course of the negotiations, all parties in the governing coalition agreed that the Law of Return would be amended within 60 days of the swearing-in of the government, and in any case no later than May, 2023.

In 1970, the Law of Return was amended to define a Jew as “a person who was born of a Jewish mother or has converted to Judaism and who is not a member of another religion.” Additionally, the more expansive definition as to who may qualify – the grandchild clause – was included at this time; specifically stating that the rights of Jews (as defined above) shall apply to their children and grandchildren, even if they are not considered Jewish according to halacha (Jewish law) and on the condition that they are not members of another religion. (The original Law of Return, 1950, stipulated that any Jew, their spouse and children of Jews have a right to return to Israel. The question as to “who is a Jew” was not parsed in that law, which was also silent on the matter of conversion.)

In the runup to the November election, the far-right Religious Zionist party expressed fears that Israel would be “flooded with non-Jewish immigrants” and pointed out that even today, the majority of immigrants to the country are not halachically Jewish. This concern by certain religious communities in Israel about the aliyah of (non-halachically Jewish) descendants of Jews is not a new phenomenon; there has been quite a lot of talk about it in the past.

But today, with the hard-right, very religious make-up of the governing coalition, there is a strong likelihood that the grandchild clause will be repealed. If so, this would have dramatic implications for continued immigration to Israel, the character of the Zionist state, and Israel’s relations with Diaspora communities.

II. Who Is a Jew, Reprise

According to data from the Ministry of Immigration and Absorption, in the last decade about 320,000 people immigrated to Israel. Most of them were from Eastern Europe, with others from France and North and South America. In 2022, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the outbreak of war, approximately 66,000 new immigrants from these two countries moved to Israel.

Towards the end of 2022 (when the Knesset's Research and Information Center published data indicating that there was a decrease in the number of immigrants who are Jewish according to halacha) a media storm erupted. Yet again, the ever-controversial question of “Who is a Jew?” was at the fore of public attention. And, with that came the companion issue: Who has the right to immigrate to Israel?

The Knesset Report stated that in 1990, 93 percent of immigrants to Israel were halachically Jewish, but that figure had dropped precipitously to 28% by 2020.

The members of the governing coalition that was being formed at the same time as this data was released relied extensively on this new information to justify the repeal of the grandchild clause. To them, it is as straightforward as a law of nature that “non-Jews” (halachically) must be prevented from immigrating.

However, even in the 1990s, when the percentage of halachic Jews among the immigrants was significantly higher, various politicians demanded an amendment to the Law of Return in order to limit the immigration of the third generation – the grandchildren. Some of the original advocates of this approach have recently made a political comeback and wield enormous power.

III. The Long-Brewing Showdown Over the Definition of “Jew”

Former MK Roman Bronfman, fought those battles in the 90s as a member of the now defunct party, Yisrael Ba’Aliyah (founded by former prisoner of conscience in the USSR, Natan Sharansky). At that time, Avi Maoz was leading the push to revoke the grandchild clause. Today, Maoz heads the far-right, anti-secular, homophobic party Noam, also a coalition partner. He was recently appointed to the position of Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office with responsibility for Jewish Identity. Exactly what that means and how it will play out remains unclear. But, it is a disturbing sign. Maoz is an extreme messianist who is virulently hostile to any form of Jewish identity other than strictly orthodox.

“There were, of course, such attempts in the past [to repeal the grandchild clause], and they were directly connected to Avi Maoz,” says Bronfman. “He was very close to Avital Sharansky (Natan Sharansky’s wife) and helped her undergo an Orthodox conversion, and he then became Natan's guide to Israeli politics. He was appointed by Sharansky as director-general of Yisrael Ba’Aliyah, and then as director-general of the Ministry of the Interior. In this role, Maoz advanced the demand to change the Law of Return’s grandchild clause. Sharansky knew about Maoz’s plans, as did Yuli Edelstein (currently a Likud MK). Marina Solodkin, Yuri Stern [Yisrael Ba’Aliyah MKs] and I firmly opposed it. In the end it never happened.”

Maoz’s setback, as it turns out, was temporary. The issue remains a priority for the religious-right.

In 2018, Binyamin Lachkar, then a member of the Likud Central Committee, wrote the following on the conservative website “Mida”:

There is no reason to continue encouraging the immigration of people whose connection to the Jewish people is questionable. The first step is to stop all acts that encourage the immigration of non-Jews from the countries of the Former Soviet Union. The second step is to change the Law of Return and limit it to [halachic] Jews and their children.

Former Labor MK Ophir Pines, also a former minister of the Interior, is well-acquainted with the period of the great aliyah from the former Soviet Union in the 90s, which was marred by frequent attacks by religious and ultra-Orthodox politicians, and their demands to stop the “aliyah of the gentiles.” He is convinced that when the legislators amended the Law of Return to include the grandchild clause, they knew exactly what they wanted to achieve, as he recently told State of Tel Aviv:

The Law of Return is not intended only for Jews, but also for their descendants. The grandchild clause is not only for Jews according to halacha – it also pertains the grandchildren of a Jewish grandfather. The idea was also to enable a return to Judaism and Jewish origins through the State of Israel. After all, we want to expand the Jewish people. Apparently, those who want to change this clause don't like that idea. And by the way, in my opinion, this clause is less ideological than it is political.

Everything in Israel is political, including immigration, especially when it involves newcomers from Eastern European countries that were once part of the USSR. Jewish life was severely suppressed there and at least three generations grew up in an environment in which atheism and assimilation were officially celebrated, not to mention the quite intense, state-sponsored antisemitism. Not surprisingly, intermarriage rates among Soviet Jews was very high, resulting in fewer halachically “pure” Jews. This issue has been the subject of much crude rhetoric, particularly among extreme right wing and ultra-orthodox interests.

IV. The Impact of the Debate on Russian and Ukrainian Immigrants

In January 2020, the Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Israel, Yitzhak Yosef, made the following remarks at a Jerusalem conference:

Hundreds of thousands or tens of thousands of goyim (Yiddish word for gentiles) came to Israel because of the ‘Who is a Jew’ law. There are many, many goyim here. Some of them are communists, hostile towards religion, haters of religion. They are not Jews at all, they are goyim. Then they vote for parties that incite against the ultra-Orthodox and against religion. They go to church every Sunday. They were brought here to be a counterweight to the ultra-Orthodox, so that if there are elections, there won't be many votes for the ultra-Orthodox. That's why they were brought here to Israel, complete goyim. To our great regret, we are seeing the fruit of their incitement.

It would appear that what lay at the core of this angry screed was not necessarily the halachic issue, but a political one. The new immigrants from Eastern Europe tended to vote for the party established by fellow immigrant, Avigdor Lieberman – Israel Our Home - or other secular and liberal parties, which, from the point of view of the ultra-Orthodox, upset the preferred balance of the political system.

Prof. Ze'ev Khanin, formerly the Chief Scientist of the Ministry of Immigration and Absorption and now a senior researcher at the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress, points out that there are oft-made claims that those who are entitled to aliyah but who are not halachically Jewish are foreign implants in the State of Israel. Khanin dismisses such comments as blatant lies with no basis in reality. “All the research I have conducted over the past 20-30 years indicates that, regardless of their religious background, within three years immigrants from the FSU have already formed their Israeli identity. They consolidate their Jewish identity within five to seven years. The rants about ‘anti-semitic goyim’ coming here are totally political.”

Khanin believes that if the government goes all out and repeals the grandchild clause, it will disrupt the current wave of aliyah from Russia and Ukraine, which were the main sources of immigration to Israel in 2022 and the preceding decades:

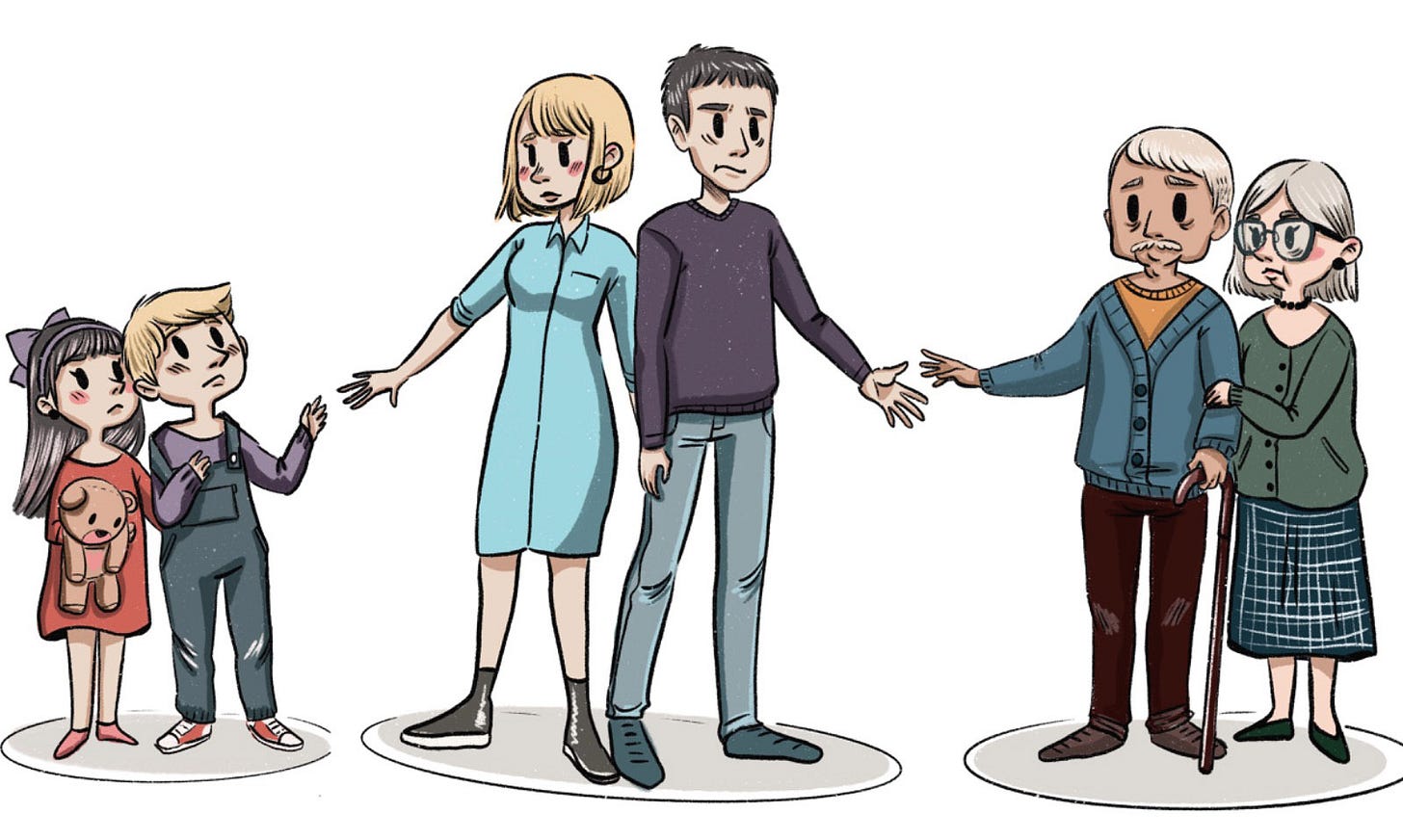

When you analyze the data for the year 2022 [during which almost 70,000 Jews immigrated to Israel, most of them from Russia and Ukraine], the adult grandchildren were not the majority. The grandchildren come here for the most part as part of a family, over or under the age of 18, along with their parents. It’s clear to everyone that the parents will not leave their children, so even the second generation, who will still be eligible according to the Law of Return, will not come, and the grandparents won’t come either. The grandchildren come together with the parents. If they are ineligible, no one from the family will come. I don't know if the government understands this or not.

V. The Government’s Conundrum: Appease Extremists or Keep the Gates Open?

According to data issued by the Ministry of Immigration and Absorption, in the last decade approximately 14,000 doctors and healthcare workers, 11,000 teachers, 9,000 researchers and scientists, and 25,000 engineers immigrated to Israel between 2021 and 2022. In all of these areas, Israel is currently experiencing a significant shortage which will only intensify.

In the 1990s as well, immigration from the FSU was a huge boon for Israel, bringing with it large numbers of these in-demand professionals. Three decades on, Israel will continue to benefit from the influx of professionals who will be loyal to the state, send their children to the army, and contribute to the economy.

The new wave of aliyah from Russia and Ukraine is expected to continue this year, with the number of immigrants perhaps even reaching 100,000. If the grandchild clause is repealed, most of these potential immigrants will go elsewhere. According to Khanin, the governing coalition will eventually be forced to choose between the more rigid definition of “Jewish”, that will cut out the “grandchildren” completely, and a more permissive definition that will allow the immigration of those who already have relatives in Israel. “Almost everyone has relatives here,” he says.

At the heart of this controversy is the Jewish Agency for Israel, the institution formed in the pre-state years with the sole mandate of encouraging aliya. Ironically, in recent years, there has been much discussion as to whether Israel still requires such an organization. The general perception is that it has become a bloated bureaucracy that adds little, if any, value to Diaspora outreach and aliya.

Last year, after a protracted selection process that dragged on for almost 18 months, Maj. Gen. (Res.) Doron Almog was named as the new chair of the Agency. Almost immediately his office had to contend with the onslaught of Ukrainian and Russian immigrants as a result of the war there, and Almog has been sympathetic to concerns regarding the repeal of the grandchild clause.

In response to inquiries made by State of Tel Aviv, Almog was unequivocal in this regard, stating that “any change in the delicate and sensitive status quo on issues such as the Law of Return or conversion could threaten to unravel the ties between Israel and world Jewry… we must do everything to preserve this unity”.

VI. What is Israel Without a Law of Return?

At the moment there is no clarity regarding the exact wording of the proposed amendment that is expected to be passed by May. In response to my direct question to him on this issue, Minister of Immigration and Absorption MK Ofir Sofer offered this rather non-committal boilerplate:

As the Minister of Immigration and Absorption of the State of Israel, I will work to encourage the immigration of Jews from all over the world, along with preserving and strengthening the Jewish character of the country. As agreed in the coalition agreements, a committee will be established with representatives from all the coalition parties, whose purpose will be to reach an agreed-upon plan on the subject of the grandchild clause; all of the many sensitivities vis-à-vis Diaspora Jews will be taken into account.

In the meantime, the government recently froze the special grants that had been given until now to immigrants fleeing from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus following the outbreak of the war. This support significantly eased and facilitated their immigration and integration process.

At the same time, approximately NIS 350 million (US $110-million) has been allocated to encourage immigration from the USA and France – countries from which relatively few have come, historically. This initiative makes clear that this government is keenly interested in promoting immigration, with a strong preference for people originating in countries with a Jewish population they consider to be more “kosher”.

As an ethical and practical matter, the NIS 350-million should have been allocated to assist new immigrants who are already in Israel and working to restart their lives. In addition to the many challenges all newcomers face, this particular cohort has been displaced by war and many are traumatized and come with no assets.

The Jewish communities in the US are demonstrating little, if any, enthusiasm regarding the government's plan to encourage aliyah from New York and Miami. Rather, they are expressing concern that the expected change to the Law of Return will deeply harm the relationship between American Jews – in particular those affiliated with the Reform movement – and Israel. In early January, the heads of seven Zionist organizations from the United States and Israel sent a letter to Prime Minister Netanyahu in which they warned of a perfect storm:

It is our duty to share with you our deep concern regarding voices in the government on issues that could undermine the long-standing status quo on religious affairs that could affect the Diaspora. Any change in the delicate and sensitive status quo on issues such as the Law of Return or conversion could threaten to unravel the ties between us and keep us away from each other.

Will Prime Minister Netanyahu agree to a change in Israel’s aliyah policy to satisfy the desires of his extremist coalition partners from the Religious Zionist, Otzma Yehudit, Noam and haredi parties? There is no escaping the fact that doing so will affect not only Israel’s demography and labor market, but also every aspect of its relations with Diaspora Jewry.

And then there’s the delicate matter that such a move would have on the core identity of a country that has until now opened its doors to those who, while not being considered Jewish by halacha, were Jewish enough to be murdered in forests and gas chambers in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s.

In 2016, MK Avraham Neguise, one of the initiators of the Aliyah Day Law (since 2016 the Aliyah day is officially celebrated in Israel) spoke eloquently of the importance of keeping the door open. An immigrant from Ethiopia who arrived in Israel in 1985, Neguise and his community pushed through extreme perils and deprivation to fulfill their wish to live in Israel. Upon arrival many were treated abysmally by the state, having their “Jewishness” questioned by the Chief Rabbinate and, often, forced to undergo conversions. The experience was humiliating and is a stain on Israel. But, they came. And most stayed.

“Aliyah”, Neguise remarked, ”emphasizes the oxygen of the State of Israel - the new immigrants - Jews who were motivated by the Zionist and biblical force to return to their native land. They, who despite the difficulties in their countries of origin, the journey and the absorption difficulties – did not flinch and stuck to fulfilling the vision, each day, using action and thought.”

Will 2023 become the year when the government of Israel decides to cut off the oxygen? We’ll know the answer soon enough.

Indeed, the Orthodox position is complicated. As is the position of new immigrants. What is problematic is the manner in which the ultra Orthodox propose to address such a sensitive topic. With a sledgehammer. The Israeli and Jewish reality is that there are consequences from thousands of years of Diaspora. They should be addressed with thoughtfulness, compassion and nuance.

Agree. And I, too, have been disadvantaged by certain changes in rules intended to address such abuses. But the issues must be managed with skill. We should try to avoid using tanks to crush mosquitoes.