War Has Consequences: 20-Year Scars of the Second Intifada

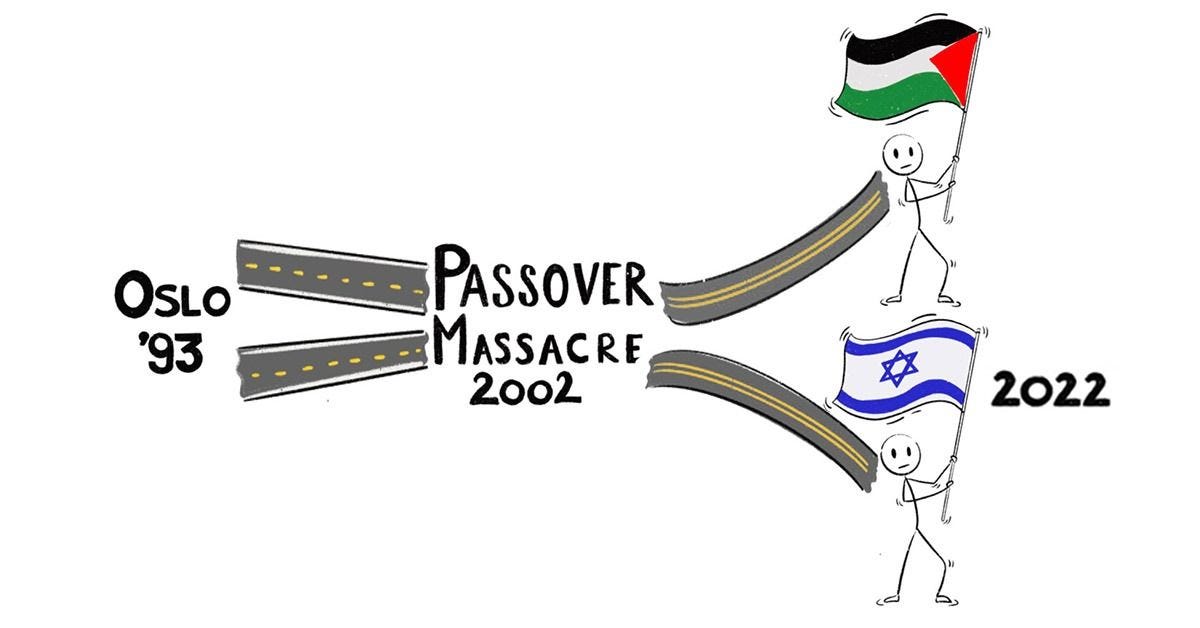

Shany Mor argues that much of the current state of play in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict can be traced back to one fateful month in 2002

Note From the Editor, Vivian Bercovici:

On March 27, 2002, a Hamas-affiliated suicide bomber entered the Park Hotel in Netanya where a Passover Seder was in progress. He murdered 30 civilians. Another 140 people were maimed and injured. Many of the attendees that evening were Holocaust survivors. For all the savagery that was unleashed upon Israelis during the Second Intifada, there was something seismic about the Park Hotel Massacre that shattered any remaining hopes among Israelis in the short-lived promise of the Oslo peace accords.

This episode marked an immediate shift in how Israel responded to the relentless attacks on Israeli civilians, known euphemistically as the Second Intifada, which raged from 2000-2005.

Shany Mor, the author of this week’s essay, is a big thinker. He is at his best when taking on the thorniest intellectual challenges and finding a way to make sense of it all. That’s what he does here; placing the Park Hotel Massacre in a broader historical context.

In this piece he discusses the arc of optimism, violence and despair that has plagued the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for the last 30 years. With the Oslo Accords came real hope for some, that there was a path to a form of reasonably peaceful co-existence. But, as we now know, that was all blown to smithereens, literally and figuratively, on the night of March 27, 2002. The gore of that night changed everything on the ground. Israeli optimism was dead. And Palestinian obduracy re-invigorated.

Shany focuses on how that violent night changed the course of history in the region. He sees the Park Hotel Massacre as a critical juncture in which Palestinians and Israelis retrenched. Palestinian leadership openly supported extreme terrorism, which many Israelis – the anti-Oslo contingent – thought had always been the case. Israelis despaired of ever achieving a negotiated peace, which many Palestinians always believed to have been a charade and shameful surrender.

Each side reverted to what had long been their default positions; that the conflict was intractable.

Shany captures the big picture issues while vividly portraying all the mundane conundrums and compromises that living in such circumstances imposes on us all.

His clarity is your reward.

Enjoy.

For most Jews, Passover means a festive meal, a Seder (or two) with family and close friends, eating matzah and retelling the story of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egyptian slavery into freedom.

For many Israeli Jews, however, reflections on the holiday this year turned to memories considerably more recent, and less hopeful.

It was twenty years ago, on the first night of Passover 2002, that the most infamous suicide bombing in Israel took place. That night, and the weeks that followed, marked a dramatic turning point in the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. The reverberations of that time still dictate the contours of the conflict today.

The months leading up to Passover 2002 were the bloodiest Israelis had experienced on the home front since the 1948 war.

This is not just a question of psychology, though it is that too. The dramatic events of those weeks left lessons to be learned for both sides, and as with all such dramas, some lessons have been overlearned. Beyond that, however, there was an irreversible change in the positions of the sides. Options for a political settlement that might still have existed before Passover 2002 and the aftermath permanently disappeared into a new reality. And rather different options that were not considered beforehand, both for a negotiated settlement and a modus vivendi in the absence of diplomacy, suddenly became conceivable.

This year, too, the Passover holiday coincided with yet another of the periodic escalations of violence between Israelis and Palestinians. The attacks themselves, as well as the whole vocabulary of the conflict, show just how deep the scars of Passover 2002 are. The different course of events thus far in 2022 is instructive too, in its own way, in demonstrating just how much was and was not learned from the traumas of twenty years back.

I. The Gloom Before the Storm: The Second Intifada

The months leading up to Passover 2002 were the bloodiest Israelis had experienced on the home front since the 1948 war. In March 2002 alone, more than 100 Israelis were killed in suicide bombings; hundreds more were injured.

Sitting at a café, riding a bus, walking through an outdoor market — everyday tasks became imbued with a feeling of danger. You made bargains with yourself about what times you would go out, where might be the safest place to sit, or whether the day after an attack was the best time or the worst time to face the danger again.

Everyone came to know the sound of explosions, and if not explosions, then at least sirens. One or two could just be a heart attack or car accident. Three or more meant you grabbed your phone and started calling your friends, your parents, anyone with whom you might have had an unresolved argument earlier in the week. Are you ok? I think something happened.

Hardcore ideologues and cranks had simple solutions, but for most people there was an overwhelming feeling of desolation and gloom. Nothing, it seemed, could be done.

The consensus that a military offensive would be folly was not just the ramblings of mushy leftists and peaceniks. It was by and large the consensus of nearly all the experts in Israel and abroad. Any operation, it was argued, would result in hundreds of casualties to Israeli forces. It would not have the support of the United States or other major powers. It would leave in its wake hundreds if not thousands of civilian casualties. And, most importantly, it simply would not work. Every dead terrorist would spawn three new ones, increasing the sense of grievance and rage that was supposedly fueling the violence to begin with.

A quirk in the domestic political situation also gave the government a lot of breathing room to pursue its strategic patience. The right-wing Ariel Sharon had been directly elected as PM in a stunning landslide in 2001 (63-37%), but without a new parliament being elected. It was the only such election held in Israel's history under an electoral law that has since been cancelled.

We know today, with hindsight, that many of these premises turned out to be false. But it is worth recalling that the arguments made were robust and accepted as being largely true back then. If Israel had embarked on a major military offensive in response to the wave of suicide bombings it had been dealing with throughout 2001, it is very likely that hundreds of soldiers would have been killed, that the U.S. would have opposed the operation, and that its success would have been limited.

But in those months of relentless suicide bombings, the IDF was making preparations. Beginning in October 2001, there were several small incursions into Area A of the West Bank, the parts that under the Oslo Accords were supposed to be under the exclusive control of the Palestinian Authority. Military tactics were honed and operational lessons were learned.

On the diplomatic front conditions were also evolving. The 9/11 attacks made any association with terrorism a liability. In the initial months after September 11, 2001, the Bush administration reached out to Arafat’s Palestinian Authority in order to shore up its credibility in the Arab world as it was embarking on its “war on terror.”

But then in January 2002, Israeli forces intercepted the Karine A, a ship laden with Iranian weapons en route to Gaza (then still under the control of Arafat's Palestinian Authority). The Bush Administration was outraged, and Arafat’s lies to the President in a one-on-one call about the shipment only made matters worse for him. Arafat, who over the previous decade had grown accustomed to the status of an accepted world leader, would never again have an open line to the White House.

Thus, as a new wave of suicide bombings began in February 2002 – a month after the Karine A incident – Israeli leaders re-assessed their opportunity to respond militarily. The public could not withstand the relentless attacks on civilians, the IDF was readier than it had been before, and the Americans were more favorably disposed to Israeli action.

A quirk in the domestic political situation also gave the government a lot of breathing room to pursue its strategic patience. The right-wing Ariel Sharon had been directly elected as PM in a stunning landslide in 2001 (63-37%), but without a new parliament being elected. It was the only such election held in Israel's history under an electoral law that has since been cancelled. Sharon came into office and inherited the Parliament that had swept in with the more left-wing Ehud Barak’s victory in 1999. The only way for Sharon to form a government was to keep Labor on board and have a broad-based national unity government, with leading dove Shimon Peres as his Foreign Minister. The lack of an effective opposition gave the government breathing room in a crisis that otherwise may have led to rash action.

II. The Tipping Point

By the time of the Passover Massacre, it seemed there was little left that could shock the Israeli public. A year earlier 21 young Israelis, mostly teenage girls, were murdered outside a nightclub in Tel Aviv in a suicide bombing. Such attacks had become commonplace and were launched in pizzerias, on buses, throughout city centers. And as Passover approached at the end of March 2002, the pace had picked up to nearly one every two days.

And yet something about that night’s deadly attack felt different. Perhaps it was the death toll, at 30, higher than in any other such attack. Perhaps it was that a third of the victims were Holocaust survivors. Perhaps it was the holiday itself that imbued it with such gravity — Jews gathering as Jews with families to celebrate deliverance from bondage into freedom. Whatever it was, a limit had been breached, and it was obvious to all that the response would be qualitatively different than anything which preceded it.

That weekend, 20,000 reservists received emergency call-up orders. In a country normally wracked with infighting, there was a brief, determined, grim agreement about the necessity of a large military offensive.

The Israeli response was not, however, supported by an international consensus. Protests against Israel erupted in all the major western capitals though, notably, there were few if any protests against the Palestinian suicide bombings.

The US was nearly alone then in defending Israel’s right to self-defense. European condemnations were swift and occasionally severe. The European Parliament passed a non-binding resolution calling for sanctions against Israel.

International media coverage of the operation was overwhelmingly negative and certain that the operation could never achieve its goals of ending the wave of terrorism targeting Israeli civilians. Major global NGOs, mobilized only a few months before at the UN’s infamous Durban Conference to dedicate their work to fighting Israeli “apartheid” and “war crimes,” issued reports employing language never used for even the worst human rights violators. The two standard tropes that accompany discussion of any Israeli military operation — Israel is harming a holy site! Israel has committed an atrocity! — were both rolled out this time.

There was never a moral or professional reckoning among the media outlets and NGOs about the fabricated reports of massacres. And the pattern of reporting which relies on a demonic archetype of Israelis, scheming, plotting, killing, covering up, was repeated again in Israel’s war with Hezbollah in Lebanon four years later, again in Israel’s war with Hamas in Gaza three years after that, and again ever since.

News reporting focused on three major events, none of which related to attacks on Israelis. The first was the IDF’s breach of Arafat’s Mukataa compound in Ramallah. Western “peace activists” later broke through to serve as human shields in the compound. In the entirety of the Second Intifada, it bears noting, no peace activists ever came to serve as human shields on Israeli buses.

The second was at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, where dozens of wanted terrorists had taken refuge, secure in the knowledge that Israel wouldn’t harm such a holy Christian site. The IDF surrounded the Church and left only after five weeks when an agreement was reached that saw most of the wanted men deported. Tellingly, this was reported at the time as an “Israeli siege” of a Christian holy site, leading to some rather explicitly antisemitic imagery in the European press.

The third locus of combat that caught the world’s attention was, of course, the Jenin refugee camp, site of a pitched battle between the IDF and assorted Palestinian militant factions. It was the site of one of the only tactical successes Palestinian forces had against the IDF, when booby-trapped houses exploded on an invading force and killed thirteen Israeli soldiers. It was soon after that rumors that the IDF had conducted a “massacre” in Jenin began.

For more than two weeks, the news of the “massacre” dominated foreign press coverage, especially in Britain. “Firsthand” accounts spoke of entire families wiped out, of the stench of bodies buried under rubble, and of active efforts by the Israelis to cover it up.

After more than a fortnight of hysteria, it became clear that there was no massacre at all. All the dead in the battle were accounted for. There were 23 Israeli soldiers and 52 Palestinians, the bulk of whom were combatants.

There was never a moral or professional reckoning among the media outlets and NGOs about the fabricated reports of massacres. And the pattern of reporting which relies on a demonic archetype of Israelis, scheming, plotting, killing, covering up, was repeated again in Israel’s war with Hezbollah in Lebanon four years later, again in Israel’s war with Hamas in Gaza three years after that, and again ever since.

III. For Israelis, a Bitter Disillusionment

The 1993 Oslo Accords were pitched to Israelis with a double promise. They would improve the security of Israel, battered by decades of terrorism. And if that first promise remained unfulfilled – even after Israel recognized the PLO and carried out the staged withdrawals from the Gaza Strip and West Bank as called for in the Agreements – then the whole world would see who the bad guys really were and stand by Israel.

Neither promise was realized and each disappointment left deep scars on the Israeli psyche.

The scars of the first broken promise are the most visible and measurable. Almost immediately after the Accords were signed, the number of attacks against Israeli civilians went up rather than down. Then came the suicide bombings. There was a brief lull in the years 1998 and 1999, but by 2000, with the outbreak of the Second Intifada, Israelis experienced violent attacks with an unprecedented intensity and frequency.

The effect on public opinion was stark. On the one hand, an enormous skepticism emerged about peace with the Palestinians. On the other, there was a growing wariness about the utility of the occupation.

This is what opened the way for a right-wing leader like Ariel Sharon to eventually undertake a large military offensive as well as a unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip (and four settlements in the northern West Bank) in 2005.

The scars of the second broken promise aren’t as visible, but they run much deeper and, if anything, weigh even more heavily on Israeli thinking. Israelis still obsessively pay attention to global public opinion, but the broad center of Israeli politics no longer is moved by expectations of global support.

It was a sobering experience. There has, in the last twenty years, emerged among the Israeli Left a healthy cynicism about the motivations of much of what passes for “criticism of Israel,” as well as about how much that “criticism” can be an argument for or against any policy.

The two disappointments together may have eviscerated the old pro-Oslo Left electorally, but they have also rendered the policy debate in Israel altogether more mature. Israel will take the steps it needs to protect its security and long-term viability, but not because of a fantasy of pacific intentions from its enemies or the accusations of its critics, but because it will be the strategically and morally right thing to do.

In later years, slowly, gradually, without any announcement or fanfare, the Intifada receded into memory, and life returned to a kind of normalcy. Security checks at restaurants and event halls became cursory and then disappeared altogether, as did fences around sidewalk cafes.

But the lessons of the two broken promises would not be forgotten.

With the outbreak of the Second Intifada, Israelis experienced violent attacks with an unprecedented intensity and frequency. The effect on public opinion was stark. On the one hand, an enormous skepticism emerged about peace with the Palestinians. On the other, there was a growing wariness about the utility of the occupation.

IV. For Palestinians, a Delayed Reckoning

The Palestinians, too, took some time to understand the meaning of the events of that spring. By that point, the Intifada was already well into its second year, and it was clear even then that it was a costly affair. It was also clear that statehood, which could have been achieved in final status talks in 2000, had been put off indefinitely.

It would take a few years for the Palestinians to understand the magnitude of their defeat. By the end of 2002, the IDF was operating freely throughout the West Bank, including in Area A. A massive fence was soon under construction, making access to Israel more difficult and reversing decades of economic integration between Israelis and West Bank Palestinians. By the end of 2004, Arafat was dead (from illness) and most of the leaders of various militant groups were either dead (by assassination) or in prison.

The rejection of statehood and descent into suicidal violence had yielded absolutely nothing positive for the Palestinian cause. Oslo had brought them the first ever Palestinian Arab self-rule and government. Palestinian passports were issued as were Palestinian postage stamps. An international airport was built and operated in the Gaza Strip. An armed force, referred to technically as a “police” force, was established under Palestinian control. Diplomatic legations opened in both Ramallah and Gaza City (a small number of these even called themselves “consulates” and “embassies”). Elections were held in the West Bank and Gaza, and even East Jerusalem Palestinians were allowed to participate, despite East Jerusalem not being in the territory allotted to the Palestinian Authority. International investment and development aid were showered on the Palestinians at a per capita rate unseen anywhere else in the world.

These were not just the symbolic trappings of statehood. They led, in fact, to final status talks at which statehood was offered in exchange for a full peace with Israel — and rejected.

V. War Has Consequences

History does not spread evenly across a surface. It has periods of plodding stability and bursts of irrevocable change. The bleak reality of Palestinian politics is mostly the outcome of three very different Arab-Israeli wars which broke out in 1947, 1967 and 2000.

The first was a year-long total war between two national communities, fought village by village and town by town, whose belligerents included militias, guerrillas and eventually standing armies. The second, in 1967, was a rapid war between modern, conventional armies across three fronts fought, for the most part, distant from civilian populations. And the third, beginning in 2000, was a long struggle between assorted militias and civilians as well as the armed forces of a state-in-the-making and an occupying army.

Each one of these wars was preceded by bellicose rhetoric from the Arab side and almost unbridled enthusiasm for a fight, with few if any dissenting voices. Each ended in a catastrophic defeat and with the memory of the pre-war ecstasy completely effaced, replaced with a feeling of victimhood and a genuine memory of having come under unprovoked attack.

And here we are, twenty years after the third catastrophe. It is gutting to realize that in 2000 there were no significant dissenting voices to the Palestinians’ decision to refuse peace with Israel and instead launch a violent campaign of suicidal terrorism, where suicide was not just a means, but something of a metaphor for the whole endeavor. It’s depressing to realize that even now, two decades after the climax of that campaign, there is still no significant voice – not even an unpopular voice of dissent – to articulate why, or even that, it was a mistake.

And it is maddening that in the broader community of pro-Palestinian activism in the West, this view is simply non-existent.

Quite the opposite: The idea that the final defeat of Israel is near if we just wish for it hard enough has never had more purchase on the pro-Palestinian intellectual discourse. With each glossy new report accusing Israel of being an inherently criminal enterprise; with each gushing proclamation of the “new” idea of a possible one-state solution (which is neither a solution, nor new, nor possible), the path to liberation grows longer and more treacherous.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please consider becoming a Premium Subscriber to State of Tel Aviv.