The Story of Adam Munz: One of 874 Jews Given Refuge in America in 1944

Or, put differently: The 0.016% of Europe’s Six Million Jews America Saved in WW II.

Today marks the shloshim* of my mother’s passing, although in some ways it feels like a year. These ancient rituals of mourning make sense when you need them, even when you are sure you do not.

As she often commented to me, my mother lived in a time that, for Jews, was unparalleled. And she was acutely aware of her place in this epic tragedy, unfolding, in real time. My mom was an avid chronicler who saved what she called her many “treasures”, which remain as a haphazard chronicle of her life.

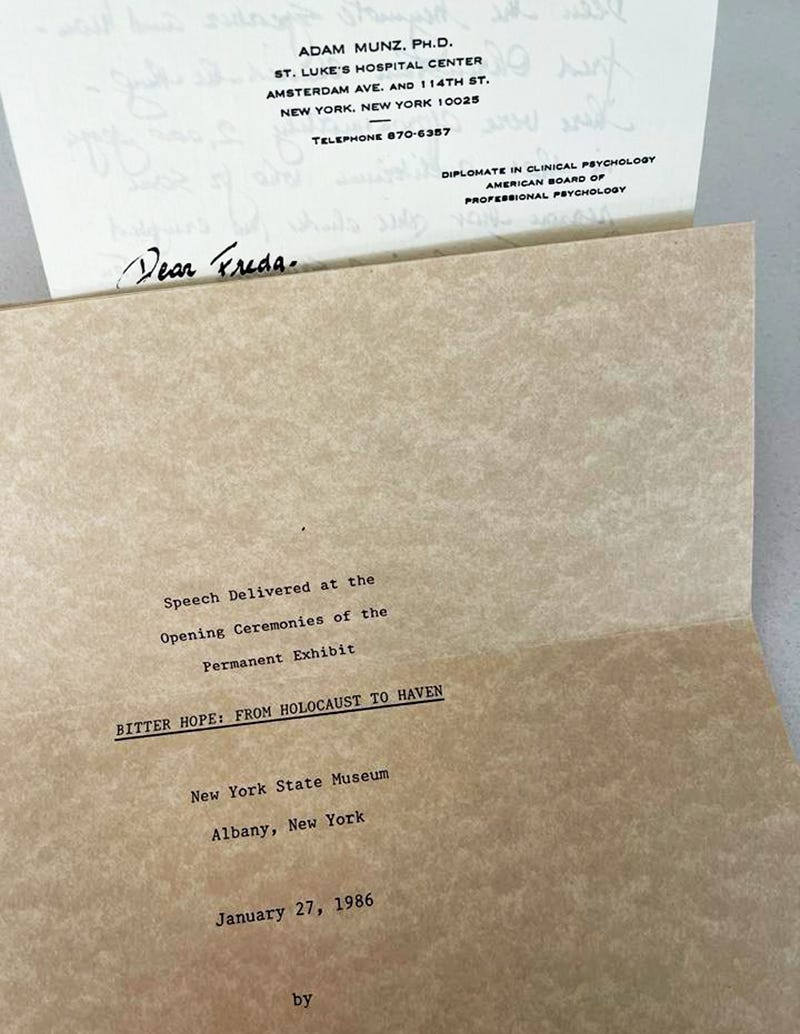

Among her papers was a letter written in beautiful script with a fountain pen. It was addressed to my mother in 1986, from one Adam Munz. A clinical psychologist of some renown – the head of Psychology at New York’s St. Luke’s Hospital – Dr. Munz passed away in 1988 at the age of 60. From the tone of his letter to my mother, they had corresponded previously. Their exchange was serious and focused on the topic of antisemitism; written in the polite but familiar tone of a bygone era.

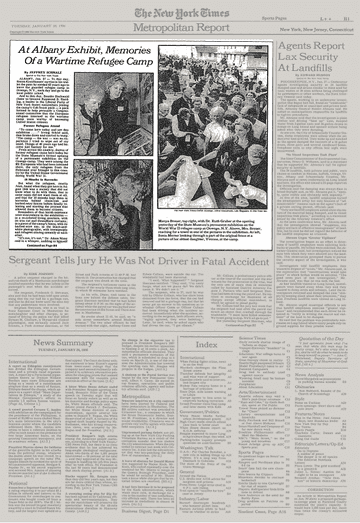

This particular letter focused on an article published in the New York Times on January 28, 1986. The report was about the opening ceremonies of a permanent exhibition – Bitter Hope: From Holocaust to Haven – at the New York State Museum in Albany, that had taken place a day earlier.

Dr. Munz was among the speakers who addressed the 2,000 guests assembled for this occasion. His remarks were brief, and a typed copy was sent to my mother on fine, textured writing paper. (Quality paper used to mean something; it communicated importance, respect and thought.)

Munz opened by telling the story of a reporter who had asked him, a few days earlier, whether he could forgive what happened during the Holocaust years. His three typed pages of remarks addressed this painful, core issue exclusively, concluding:

“I assume no responsibility for my inability to forgive them…that is a component in me that died more than forty years ago. I blame those Germans, those Nazis and their cohorts who robbed me of many things, including whatever capacity I might have had to forgive t hem. They killed and warped a very precious component of humanity. I, for one, can neither forget nor forgive!

“Those of you who know me know that I cherish life and freedom and that I try, in my work. To promote these precious aspects in others. Those who know me also know that I deeply mourn the fact that neither life nor freedom will ever again be what it could have been for so many, many millions. A piece of the fabric of society has been evulsed** forever. That. For me, is what the solemnity of this occasion is all about!

The exhibit documented the extraordinary story of 982 refugees spirited to the United States in 1944 by special order of President Roosevelt. He had, in fact, made allowance for 1,000 people but at the last minute eighteen bolted. The refugees feared that to board the ship in Naples that they were being told was destined for America was just another ruse. Another death trap.

Among the passengers on the massive vessel - Henry Gibbins -was Ruth Gruber, a young Brooklynite who was working as a Special Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes. Gruber describes Ickes as having been the only member of the wartime administration who was moved to do something, however small, to address the mass murder of Europe’s Jews.

It was another era, when people met face-to-face, and kept notes, and paid attention in a different way. With compassion, brilliance, cunning and unceasing professionalism, Gruber accomplished the impossible, repeatedly. From her telling (in her book on this period, Haven, which I recommend highly), she did so with the full confidence of Secretary Ickes. Ultimately, their joint persistence restored a measure of dignity to 982 refugees, 108 of whom were not Jewish. President Roosevelt, reportedly, did not want to be perceived to be approving an exclusively Jewish rescue operation.

The entrenched antisemitism at the time in the American government, corporate and academic elites was virulent. (The same, incidentally, goes for Canada, where wartime Prime Minister, Mackenzie King and his Minister of Immigration, Frederick Blair, were staunchly opposed to doing anything to address the Jewish crisis. In fact, in a bombshell book published in 1983, Canadian historians Irving Abella and Harold Troper exposed the deep antisemitism that had permeated Canadian institutions. Canada, they contended, did the least of any western nation to alleviate Jewish suffering (and that is a low bar to start with). The PM, his close associates and the French and English-speaking elites (the social nomenclature of power in the country – then and now) were guided by the phrase that “none is too many” when it came to admitting Jewish refugees to Canada.

“None is too many.”

Wartime Canadian PM Mackenzie King and Minister of Immigration, Frederick Blair

In this generally hostile environment towards Jews, which permeated Washington D.C., Ruth Gruber was an anomaly; steadfast in reminding all with whom she worked of the ongoing horror of the mass murder of more than six-million European Jews, about which America seemed unfussed. The camps, gas chambers, mass shootings in forests, horrific asphyxiation of millions with various methods in sealed trucks, organized starvation and extreme persecution; all this was well known in the west by the time President Roosevelt decided to save 1,000.

Even still, the operation was controversial. Accommodating refugees on the ship meant that one thousand wounded U.S. servicemen would remain in Italy a while longer, which was not a popular decision.

The planning that allowed the transport of the 982, however, was meticulous. The refugees boarded the Henry Gibbins, a ship that was in the center of a large flotilla, including 16 troop and cargo vessels escorted by 13 warships. Perhaps most important were the two warships transporting thousands of German POWs, which served as human shields to prevent attacks from the air by the Luftwaffe and at sea from the dreaded German U-boat fleet. There were harrowingly close calls, but we know how the story ends.

Once ashore in New York, the refugees were transported to a re-purposed army camp in Oswego, a town of 22,000 in upstate New York, on the shore of Lake Ontario.

The German POWs were scattered across America to labor on farms due to the quite desperate manpower shortage. Among the ugliest ironies, which Gruber refuses to let us forget, is the fact that throughout the war, the United States admitted only 874 Jewish refugees, whereas approximately 400,000 Nazi POWs were brought over as farm laborers.

I find that unfathomably difficult to process.

Upon arriving in New York, the refugees were surprised - and terrified – to be treated rather harshly. They remained on the ship for their first night at dock. The following day, men and women disembarked and were separated. All were required to strip naked in the presence of male soldiers, who then sprayed them head to toe with DDT disinfectant. At the same time, their clothing was similarly cleansed and returned. They were then required to wear a cardboard tag hung on string around their necks, which stated: “U.S. Army Casual Baggage.” Each person was assigned a number. No names. They were then escorted.

To a train.

If one tried, a more insensitive “welcome” could not have been devised.

I mean. Yes. It was wartime and all. And it was a different time. But this process was blood-curdlingly insensitive. By 1944, everyone – the refugees, Allied military officials and certainly the American government – knew what had been done and continued at full throttle: the mass murder of more than six million Jews. And they were well aware of the use of trains, cattle cars, degradation, humiliation and “delousing.” No one can now or could then plead ignorance.

The 982, infants, elderly, infirm, travelled north to Oswego. They were housed in a repurposed, spartan army camp, called Fort Ontario, which was surrounded by a fence topped with barbed wire. For four weeks they were kept in strict quarantine, not even allowed visits by family members already living in the U.S.

Following the initial shock at being lightly incarcerated, the 982 developed a way of living, which was mostly about waiting for the war to end so that they could resume some degree of normalcy. These were people who wanted to work and learn and contribute to society but were prevented from doing so, resulting in a rather serious group depression. All were boundlessly grateful at having been saved but collectively felt they were existing, not living. Yes. They were safe and alive. But they were also not free, Gruber writes, and that was the fundamental imperative for most.

The most fortunate were the children and teenagers who were allowed to leave the compound daily to attend local schools. Their English improved and their days were purposeful, unlike those who languished in suspension.

Before departing from Italy, the refugees were required to sign some sort of form agreeing to return to their country of origin at the end of the war.

When the war did finally end and the U.S. authorities seemed intent on forcing the 982 to repatriate, anger and disbelief were intense. How, Gruber asks, do you force a former Polish Jew, whose town was now located in the post-war Soviet Union, to return. To what? After unprecedented human and physical devastation, when tens of millions of Europeans were displaced (scholarly estimates range from 50-80 million), how does someone in America decide to pretend that things in 1945 are as they were in 1939? And why go to such lengths to torment a mere 982, especially in the context of millions murdered?

For months, American officials persisted in adhering to the “agreed upon” process, at one point going so far as to say that the 982 could be sent back to the part of continental Europe controlled by America and – since virtually all would be eligible to enter the U.S. under postwar refugee quotas – they could apply anew. It seemed like an awful lot of silly process to underscore the seriousness of U.S. political bureaucracy.

During months of tension as their present and futures remained in limbo, dozens of the 982 did return to Europe and it is a certainty that they regretted having done so. Most ended up repatriated to newly communist countries – Yugoslavia in particular - and would likely have been ostracized due to their time spent in capitalist America. We know nothing of them but can surmise.

The refugees who remained and became American citizens, overwhelmingly, lived with endless gratitude for having been rescued and were deeply motivated to contribute to their new home.

Among them was Adam Munz, my mother’s correspondent, who wasted no time in chasing and fulfilling his American dream. And who was acutely aware of his luck in being rescued. And his responsibility to those whose dignity and lives were destroyed so brutally.

* “Shloshim” is a Hebrew term referring to the passage of thirty days from someone’s burial. Immediate family members are understood to be in mourning during this time and typically will not participate in festive occasions in order to ease their way back into a more regular rhythm of life.

**I, too, had no clue what this word means. “To extract with force/forcibly.”

I wonder how many unknown Holocaust stories like this one exist in America's dark dusty basements. There is so so much we don't know, so much information that has been withheld from so many. Thanks so much for sharing this story, Vivian.

This story seems minor in the context of the murdered 6 million, but it's not. It's a part of that context that was obscure until now. Thank you for bringing it to light.