The Heroism of Roni Eshel: What Really Happened at Nahal Oz IDF Base, October 7th

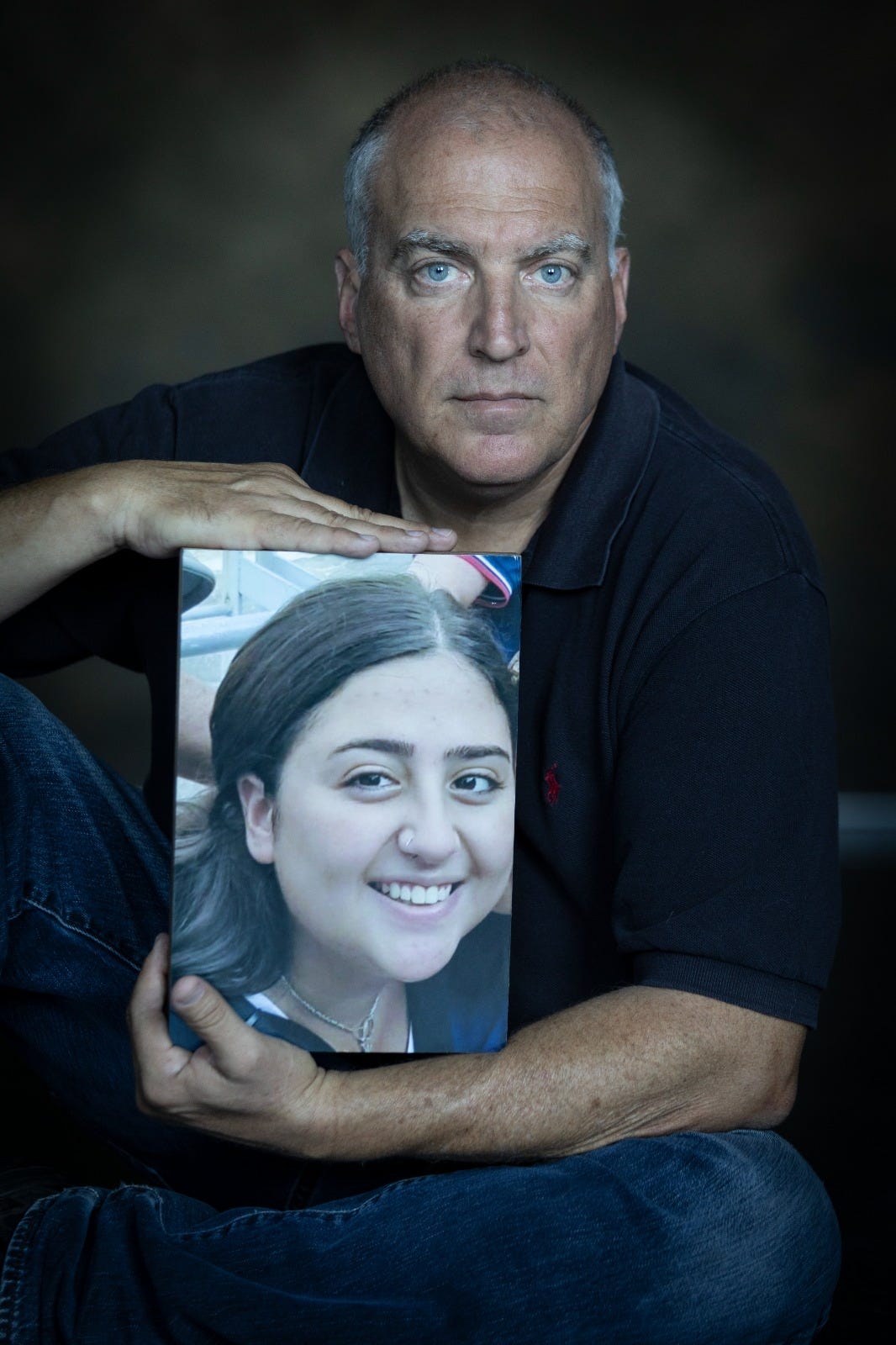

Two weeks ago, I met Eyal Eshel on a park bench in Herzliya, a middle-class city just north of Tel Aviv.

He is a common uncommon sight these days in Israel; a man in his 50s sporting IDF “greens”, as Israelis call the army uniform of the rank and file. In spite of there being no legal requirement for him to serve in the reserve forces at his age, Eshel, like so many “older” Israeli men, has chosen to step up in this dreadful time.

A father of three, his 19-year-old daughter, Roni, would have turned 20 on March 4th, had she not been murdered by Hamas monsters five months earlier. Roni was one of a small group of IDF intelligence officers serving as a “scout” at the Nahal Oz base in southern Israel. She and her team of female soldiers spent their days and nights staring at surveillance screens of a defined area of a very small land in the Gaza Strip abutting the border with Israel. I have visited these bases on numerous occasions, including when I served as Canada’s Ambassador to Israel from 2014-16. One young woman, I recall, explained to me that if a rock moved a few centimeters in her “area” she would notice immediately. Consider that this land, when not cultivated, is desert. Sand. Small rocks and stones. Everything is camouflaged by the muted desert palette, strong sun, flat landscape. It is a grueling job and one at which the scouts – known as “tatzpitaniyot” in Hebrew – excel.

These young women are selected based on a rigorous assessment process. Apparently, there is extensive scholarship – and empirical evidence - demonstrating that women are far more attuned to visual detail and observation than are men. And so, it was decided in the IDF that keeping eyes on Israel’s borders would fall to the women.

Their commanders, however, tend to be men. And, by all accounts, at the Nahal Oz base, there were some pretty hard-baked chauvinists.

Roni, her colleagues and a female commander had been observing alarming developments along the border with the Gaza Strip for much of the preceding year, and longer. There have been multiple, detailed news reports of the scouts waving red flags over highly unusual training drills undertaken by elite Hamas fighters over a prolonged period of time. In broad daylight. Right up against the border with Israel. Paraglider training. Drills in which they stormed mock kibbutz gates and army bases. Replicas of guard towers found on the Israeli side of the border were “attacked” in military exercises in the Gaza Strip. It was all out in the open. Brazenly so.

Then there was the long, detailed document in Arabic that IDF military intelligence obtained and analyzed a year prior to October 7th, which set out in granular detail how Hamas attacks would unfold. It was a very long, meticulously written report about this Hamas document was dismissed by senior IDF officials.

Repeated reports submitted by the scouts were disregarded by senior IDF officials. Hamas, the scouts were told, were a bunch of punks. Their “plans” were fantasies.

Major General Aharon Haliva, the Head of the Military Intelligence Directorate for the IDF, supported his subordinates in dismissing the reports of the scouts. A female commander at the Nahal Oz base was actually threatened that if she continued to press her concerns she would be court martialed.

On the night of October 6th and into the early morning hours of the 7th, the top brass of the IDF and Shin Bet Security service were alerted to a number of extremely serious developments. Several thousand Israeli SIM cards were reportedly activated in the Gaza Strip, simultaneously, around midnight. Since so many men from the Gaza Strip crossed into Israel on a daily basis to work in the agricultural industry in the south, they often used Israeli SIMs to facilitate communication while they were within the country. But typically there would be tens, maybe a few dozen SIMs activated in the course of a day or night. But not thousands. And not at exactly the same time. And certainly not on a Friday night. No one would be entering Israel from the Gaza Strip on a Saturday.

Eyal Eshel asks, pointedly: “Why were so many people talking on their phones and walking in the streets in Gaza? At midnight? They (IDF and Military Intelligence) knew something was up. And there were other things going on that we still can’t speak about.”

But after at least one middle of the night phone call - the men entrusted with keeping Israelis safe within the country’s borders - decided to get some sleep and reconvene at 8:30 on the morning of Saturday, October 7th.

In the meantime, Major General Haliva was in Eilat on holiday. When contacted by an underling he asked that no one bother him further until after 9 am.

By that time, Roni Eshel was in Hell. Her family, at home in central Israel, was in the dark. They were glued to their television at home. Something very serious was going on in the south. That much was clear. And Roni was not answering her phone. They knew that she often did early morning guard duty at the base. But…

On Wednesday, October 4, Roni was at the front door of the family home, waiting for her mother to drive her to the train station to return to her base after a short holiday. Eyal went to hug his daughter and say goodbye.

She was not her usual self. Roni was worried. Very worried. IDF soldiers are notoriously tight-lipped about their duties. “It’s boiling over there, dad,” she said. She had been watching this nightmare unfold before her eyes for too long and she was terrified that something horrific was about to transpire.

For months, Roni had been telling her father and mother. “They – Hamas – know everything about us. They have tons of intelligence.”

She told her parents that being at the Nahal Oz base was very scary. Eyal and his wife, Sharon, know today that all the girls were equally troubled and confiding their dark fears to their parents. Roni was one of the longest serving among the fifteen young women at the base. Seven were taken hostage by Hamas. At some point in November, 19-year-old Noa Marziano was murdered in captivity. Ori Mogadish was rescued by the IDF on October 30, miraculously. The rest were murdered on October 7th.

Eyal told me that as he parted with his daughter on Wednesday, October 4th, at the entrance to the family home, he put his hand on her shoulder.

“I said: ‘Roni. We have a strong army. Don’t worry. We have a good army.’” That’s the last time he saw her.

“I thought nothing would happen,” he says, months later. “I had no idea how many officers refused to believe there could be such a disaster.”

Roni’s mother drove her to the train station in Kfar Saba for the journey to Sderot, near the Nahal Oz base. That phrase – “it’s boiling there” – is something that Eyal said she had been repeating for months. All the scouts knew that there would be a scenario involving a Hamas invasion of Israel. Everyone knew. The scouts were even briefed by their commanders about this. And they were told that in such a situation – if their base was invaded – that they were to hide in the dining room.

Hide in the dining room?!?!?

The female scouts had no weapons. The male soldiers on base were meant to protect them.

“How can this be?” I asked Eyal.

“You see?” He replied. “That’s part of the failure. The story. The war room wasn’t prepared. They didn’t take care of the soldiers. There was a total failure by the higher-ups to do their jobs.”

But on Wednesday, October 4th, Eyal was not aware of the scope of the disaster. He reassured Roni. “This is the IDF. The best in the world. They know what they’re doing. Don’t worry.”

Roni Eshel was returning to base as one of the more experienced scouts to welcome new recruits who were spending their first weekend at Nahal Oz. Roni loved to cook and, Eyal beams, she had “golden hands” in the kitchen. She was amazing with Asian food, home-made sushi. She rolled out hand-made pasta with a special machine. On her final Friday night at the base, she cooked for her fellow scouts.

Among the new soldiers at Nahal Oz was Na’ama Levy, a lovely 19-year-old young woman from central Israel. On the morning of Saturday, October 7th, a video clip of her went viral, globally. Na’ama, violently pulled by her long hair from the rear of a jeep by an armed Hamas monster. Her face was sheer terror. Blood had dried on her face, arms, where the savages had cut her Achilles tendons so that she could not run away. Her light grey sweatpants were soaked through with blood on the bottom. It does not take much imagination to realize what had been done to her. Not even her parents recognized her initially.

Na’ama was dragged to the back seat of the jeep and shoved in between two Hamas thugs. All the while the jubilant mob of civilians – men, women, children – were shouting “Allahu Akhbar.” Gaza City had erupted in celebration.

That was 167 days ago. Na’ama is one of 19 women, most of them in their late teens and early 20s, still being held by Hamas in the tunnel dungeons. There is a surfeit of evidence – testimonials, video, audio and forensic – verifying the horrific allegations of war crimes carried out by Hamas and Palestinians from the Gaza Strip on October 7th. And every day since. In the underground prisons in the Gaza Strip.

Eyal Eshel is an early riser and Saturday October 7th was no exception. He went out to walk the dogs just before 6 am and his phone soon lit up with media notices and “red alerts”, a phone application for Israelis that provides warnings of incoming rocket attacks from the Gaza Strip in the south or Hizballah in the north.

He rushed home and turned on the television. Tried to reach Roni on the phone. There were already surreal scenes on TV of white Hamas pickup trucks barreling down the highway towards the desert cities of Ofakim and Sderot. Kibbutzim were being attacked. Young partiers at the Nova music festival were massacred. Everywhere. All day long. Murder. Mayhem. Roni did not answer her phone. They knew nothing. They did not have the phone numbers of her commanders. Of the base. Of the Southern Command. Nothing. Nowhere to turn and no one to call.

Saturday night Eyal and Sharon joined a group of all the parents of scouts at the Nahal Oz base. Not a single parent had any information regarding what had happened to the girls.

They heard nothing from the IDF. All day. All night.

The following morning Eyal and Sharon went to the Lahav 433 HQ – a special police unit – to report that their daughter, Roni, was missing. Next, they drove to Soroka Hospital in Be’er Sheva. Perhaps she had been injured and taken there, they thought. Nothing. Battles with Hamas terrorists continued to rage throughout the south, so they were unable to travel to her base. They returned home. Bereft.

“I understood then that we were alone,” Eyal recalled. “I started to do a little investigating. Still. No one from the IDF contacted us.”

His shock and disbelief at the sheer chaos and abandonment they felt and experienced is still fresh.

“Part of the total failure….until today…we always thought that we were the best…. the strongest and best army….and it seems that we were wrong. We paid the biggest and most horrible price….families are being torn apart, destroyed…from the hostages not coming home. Among the remaining 134 hostages are the five girls from Nahal Oz…some of whom Roni welcomed to the base two days before the invasion. The girls finished their course on Wednesday afternoon. On Thursday they brought them by bus to the base. Some went to Re’im. Some to Nahal Oz. Some to Kissufim.”

These are small army bases (there are also nearby kibbutzim with the same names) located within a reasonably small geographic area.

“And they did such important work,” Eyal says. “In the end they saw everything first. They heard. They wrote reports. But no one thought to do anything with these reports….another part of the failure.”

“This is not like the other wars,” Eyal stated, matter-of-factly. “This one was entirely preventable.”

They knew. And did nothing. And, unlike 1967 and ’73, “they” also knew that civilians would be targets in an invasion, not just the military. This level of civilian threat was unprecedented.

Everything about that day is impossible to comprehend. Not just the barbarism. But the glee. The way Hamas “soldiers”, criminals and regular civilians reveled in sadism and torture, devoid of a shred of compassion.

Roni had two siblings, Yael and Alon, both high school students. “Two days ago,” Eyal said softly, “Roni would have turned 20.”

His bereavement is palpable. His controlled fury. I feel pain. Everywhere. I tell him that I’m sorry. I’m so sorry for his loss.

He fixes his piercing blue eyes on me like lasers.

“You are not the right person to apologize. You are not one of the guilty people responsible for this inferno on October 7th.”

Just this past Wednesday, Eyal and Sharon Eshel agreed to release recordings of Roni speaking on her army radio that. morning. From 6:29 am, she issues repeated warnings. She remains cool but the urgency in her voice is building as she sees more and more Hamas terrorists crossing the border and heading for the Nahal Oz base. Her mother speaks of her bravery. Roni, she says, does not cry. She remains professional in the most terrifying circumstances imaginable.

Eyal and Sharon have made themselves available in the last two days for multiple media interviews in Israel. How they compose themselves, contain their grief, is heroic. But they do so out of the most profound love. For their deceased daughter. Their two surviving children. Their love of family and country. And their determination to ensure that those who failed their daughter, and thousands of others; that those who failed the state of Israel in its most fundamental duty and purpose, that they all face justice. Whatever that may be.

In the coming days, State of Tel Aviv will be posting a selection of the Hebrew language interviews with Eyal and Sharon Eshel, with English subtitles.

Eyal recalls his own shock on October 7th, and to this day. “Now, we know that there were many officers who knew. And did nothing. They were not soldiers”, he says with contempt. “Combat soldiers – part of their mission was to guard and protect the girls. They were stationed just over 700 meters from the border. A nine-minute walk. They were not armed.”

“On October 7th there was not a single commander in the area. They did not sleep there. And there was no plan to save the girls. Their (the commanders’ and generals’) detachment was so total. They didn’t do anything.”

The SIM card story broke in the Israeli media in late February. Asked what he might have done on October 6th or 7th had he known then what we do today, about thousands of SIM cards having been activated at midnight, Major General Haliva reportedly told colleagues that such information would not have caused him to change his assessment on Black Shabbat. (He also said that only a few dozen SIM cards were involved, which media reports dispute.) When I mentioned Haliva’s comment to Eyal Eshel, on the park bench, he was shocked. I, too, was shocked, when I heard about it for the first time.

Eshel was heroic in managing his rage. He said that he will not speak about Haliva. And yet.

“That he is still saying these things ….”, he paused. “That they wear the uniform to this day – Herzi Halevi – the most senior person in the IDF…..he should have done something the first second that he received information - that night and in the months before. They were all asleep. They decided that nothing would happen. Everything was pink and green. and the sun rose in the morning and the birds tweeted. But no one took the information and looked at it carefully to understand what could happen there.

“I can’t understand. I can’t accept the fact that so many people whose duty it was to protect and serve in the army betrayed so many. I lost Roni. Because other people did not fulfill their duties in the most responsible way. I will not be silent for a minute. Not until every relevant fact is exposed. Anyone wearing that uniform who did not do their job had no respect for all the soldiers who were murdered and raped and burned and taken hostage in the most horrific way possible.”

Throughout the early morning hours of October 7th there were several urgent conference calls. In one, which ended sometime around 4:30 or 5:00 am that Saturday, IDF Chief of Staff, Herzi Halevi, suggested that they get some sleep and resume at 8:30 am.

“We’ll speak in the morning,” he said.

“That decision cost us dearly,” says Eyal Eshel. “We paid the highest price. They knew. Everything. But they were not smart enough to say: Stop. Let’s pay attention and make some correct decisions.”

“It is so difficult. To know that these girls waited for help. From shortly after six in the morning until around noon. They called everyone they could to come and save them. But no one came to save them.”

Roni and several others were burned to death. Asphyxiated with toxic gas.

Perhaps it is a small mercy that no one will ever know the details of what transpired that morning. There is a reason that the elite Hamas fighters who attacked the Nahal Oz base ensured that the girls’ remains were destroyed by a fire so ferociously hot that only the smallest traces of DNA remained. Fire accelerant ensured complete destruction. Of evidence. Every detail had been thought through, ahead of time. They were very well-prepared.

For 34 days the Eshel family waited. They knew nothing about Roni. Was she dead? A hostage? What had happened? The IDF knew nothing. “She might as well have been in outer space,” said her father.

And then, on November 9th, an army rabbi arrived at the Eshel family home. Everyone in Israel dreads that knock on the door. The Rabbi told them that Roni’s remains had been identified from DNA. She had been murdered on October 7th.

There was a funeral, followed by seven days of mourning.

“This crime,” Eyal says, staring off into space... “we won’t be quiet until these people are fully investigated and judged.”