The Israeli Election Guide for the Perplexed, Part 2

In Part 2 of this Israeli Election Guide from State of Tel Aviv, Vivian Bercovici breaks down the centrist and left-wing political parties running in the 2022 election

The Center and the Left

When then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu accused Avigdor Lieberman, hard-right secular leader of the Yisrael Beitenu (“Israel Our Home”) party of being a “leftie,” it was meant as a supreme insult.

Lieberman sneered in response. “I’ve lived in Nokdim (a West Bank settlement) for 30 years but the big hardliner (a jab at Bibi) lives in Caesarea.” (The latter is a wealthy, seaside resort town north of Tel Aviv. In fact, the only golf course in Israel is located there.)

Historically, the Left has been comprised of, well, left-wing parties. In recent years, though, the concept of “left” has been skewed by Netanyahu and others to refer to anyone who opposes them.

This brief introduction to the centrist and left-wing parties in Israel will focus on the actual – not phantom – parties and issues on that part of the political spectrum.

A refresher on the right wing may be helpful to putting it all together. Our earlier coverage of those parties can be found here.

I. A VERY BRIEF AND HIGHLY SELECTIVE HISTORY OF THE ISRAELI LEFT – PART 1

The Israeli Left – which founded and controlled key institutions and government for the first 30 years of the state’s existence – has become a bit of an all-purpose punching bag in recent decades. Its most recent peak was in the early ‘90s under the leadership of prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was assassinated by an extremist who saw the Oslo Accords as an unbearable betrayal of Israel.

Over the following decade, as the peace process was discredited and unraveled, Palestinian violence crescendoed with the four-plus-year Second Intifada. From 2000 to 2005, approximately 1,000 Israelis were murdered by suicide bombers attacking civilians. Thousands more were injured. The nation’s psyche was shattered, as Shany Mor wrote about so movingly in his recent essay.

Since 2005, there have been ups and downs for the Left in Israel, but the trajectory is a negative slope. The party of Founding Father David Ben Gurion now struggles to hold onto 7 of 120 Knesset seats. Currently led by Merav Michaeli, the Labor base is very small, shrinking, hardcore and tends to be on the older side. Unlike much of the western world, younger Israelis are more inclined to be right-wing than left, an interesting trend that makes sense when you consider that many came of age during the Second Intifada.

Which brings us to the really interesting part of all this: What, exactly, is the “Left” in Israel these days and how is it distinguished from the Right?

II. ONE STATE, TWO STATE: A DEFINING ISSUE OF THE LEFT

In the early 90s – the heyday of Oslo Accords negotiations and optimism – the phrase “two-state solution” became the sine qua non of any “serious” discussion of the Palestinian-Israeli future. The Accords referred to two states throughout, but they did not contemplate two equal, sovereign states. Not by a longshot.

Palestine was always to be demilitarized. It was understood by all parties that Israel would maintain a permanent security presence in the Jordan Valley, bordering the Kingdom of Jordan. According to a complex plan, Israel would have full sovereignty in certain areas, the Palestinians in others, and there would be mixed governance in the rest.

The simplest way to explain it is that Palestine was to be an independent state with respect to all matters but military, security and defense.

Over the years, though, various interlocutors became lazy with how they threw around the term “two-state solution.” It morphed into the view that there would be two sovereign states with no limitations on the Palestinian exercise of authority. Perhaps the strongest proponent of this inaccurate interpretation was former Secretary of State John Kerry. As the powerful top diplomat of the Free World, Kerry’s cavalier use of the term in this way pretty much ensured its adoption universally. His fundamental misunderstanding of the limitations of “two states” baked into Oslo was highly problematic. He just kind of made up his own version of the phrase and it became the solution du jour.

When the centrist and left-ish parties in Israel refer to “two states” they – with the exceptions of Arab parties and far-left Meretz – refer to the Oslo concept. That is what they would adhere to and advocate making their position on this issue indistinguishable, fundamentally, from that of the center-right and right-wing parties.

This is the core issue in any Israeli election today. All roads lead to this juncture and how it is addressed: Will the state remain Jewish and democratic or stumble into a situation where the occupation of the West Bank continues, compromising Israel’s democratic bona fides? Or, will it remain truly democratic and separate into two states? Another option, of course, will happen over time if the situation is not consciously addressed; that Israel will become one state, including the West Bank, but with a very mixed Arab and Jewish population. The West Bank Arab population would either become full citizens of Israel with equal rights or they would continue to live in a society governed by different laws. The character of such a nation would, of necessity, be very different from the Israel envisioned by its founders and what stands today.

III. A VERY BRIEF AND HIGHLY SELECTIVE HISTORY OF THE ISRAELI LEFT, PART II

The collective ideal permeated everything about the “Yishuv” and post-Independence Israel. [1]

Collectivism was the preferred model for state institutions and economic enterprise. Agriculture was the economic foundation of the fledgling state and kibbutzim – collective settlements that were set up like miniature socialist states – the basis of the agricultural sector. All assets belonged to the kibbutz and every aspect of life was communal; children were raised together in a special dormitory, jobs were assigned by a powerful secretary, meals were prepared and taken in a communal dining hall.

With its roots in European socialism and communist movements, the kibbutz population was almost exclusively comprised of Ashkenazi Jews. Kibbutz members and their children were seen as the best of the best; selflessly building the nation and personifying the New Jew; the bronzed, brawny Jew with dirt under his nails who was emancipated from the dreary life of incessant religious study of his forefathers. The kibbutz children were paragons of good health, good looks and, not surprisingly, tended to be drafted into the elite combat units in the army and air force. Whereas North American students vied for acceptance to top colleges, Israeli youth competed to be drafted into the most demanding army units.

Then, there was the organization of labor and economic institutions. It is impossible to overstate the centrality of the Histadrut to the founding and flourishing of Israel. The Histadrut organized workers and the economy, providing a degree of stability and planning that was desperately needed.

Left-ish sensibilities are deeply embedded in the national DNA. So much so that when it has appeared – as in this upcoming election and previous contests – that one or more of the left-wing parties may not cross the Knesset threshold, Israelis rallied to ensure that they did. It is unthinkable, to many, that the founding parties be wiped out.

The precipitous decline of the Left really gained momentum in the mid-to-late 80s, when hyperinflation ravaged the economy and the First Intifada shook the nation. Being a peacenik became more and more difficult while the potential peace partners were bombing civilian buses and cafes.

And then Oslo happened. For many, it allowed for a surge of optimism that a negotiated peace was actually achievable. And then there was the murder of PM Yitzhak Rabin. And then the Second Intifada. And all these events dealt lethal blows to the Left. This scenario also contributed to the rise of the centrist Yesh Atid party, which has become a comfortable home to many Labor party refugees.

These days, the former jewels in the Israeli crown – the kibbutzim – have been, for the most part, drastically reinvented along market economy principles or become rundown, sad little places; resembling old paper mill towns in North America long after the paper mill shut down.

Thriving kibbutzim often still have a hand in agriculture but have become appealing sites for other industries to locate. The kibbutzim themselves have developed secondary industries which more often than not have no connection to their agricultural roots.

Israel’s voting demographic is flipped compared to the voting demographics prevailing in western democracies. In Israel, the older voters are more inclined to vote left whereas younger voters are increasingly leaning to the right wing. There are many variables driving this countertrend, with security not necessarily being the most influential. The growing communities of religiously observant, and extreme, account for much of the right-wing trend. The older cohort which carries a deeply embedded residual respect for the sacrifice, vision, determination and accomplishment of the founding generation is what keeps the Left going. Without the collective ideology it is a certainty that the nation building enterprise would not have been nearly as successful as it was.

IV. KEY ISSUES FOR THE ISRAELI LEFT

In most democracies, the Center and Left prioritize issues related to social justice, economic management and regulation and, increasingly, the environment and climate. In spite of noble efforts to highlight such matters Israel always reverts to the topline issue: The Conflict (with the Palestinians) and security, more broadly. Without secure borders and domestic control over terror attacks within Israel, nothing else matters.

And on this issue, opinions and worldviews seem to be very entrenched among the Israeli electorate, with little “swing” vote to woo. Additionally, the Left has lost much of its luster. Many who voted in previous elections for Labor or Meretz, for example, did so out of a concern that otherwise the parties might not cross the threshold, and any credible democracy requires some representation from all perspectives on the spectrum. The Left sits as more of a respectful nod to the past than any recognition of a strong popular consensus in the present.

V. PARTY BY PARTY

YESH ATID

Knesset #24 – 17 seats; currently polling at 22-23

With 17 mandates and polling consistently to take 22-23 in the upcoming election, Yesh Atid seems to have a firm hold on the second largest party – in terms of Knesset seats – after Likud. The party has also established itself as the leader of the center-left camp; one that has the power and political savvy to negotiate a successful coalition and execute. The “change government” created by Lapid – no matter one’s political affiliation – was earth-shatteringly bold.

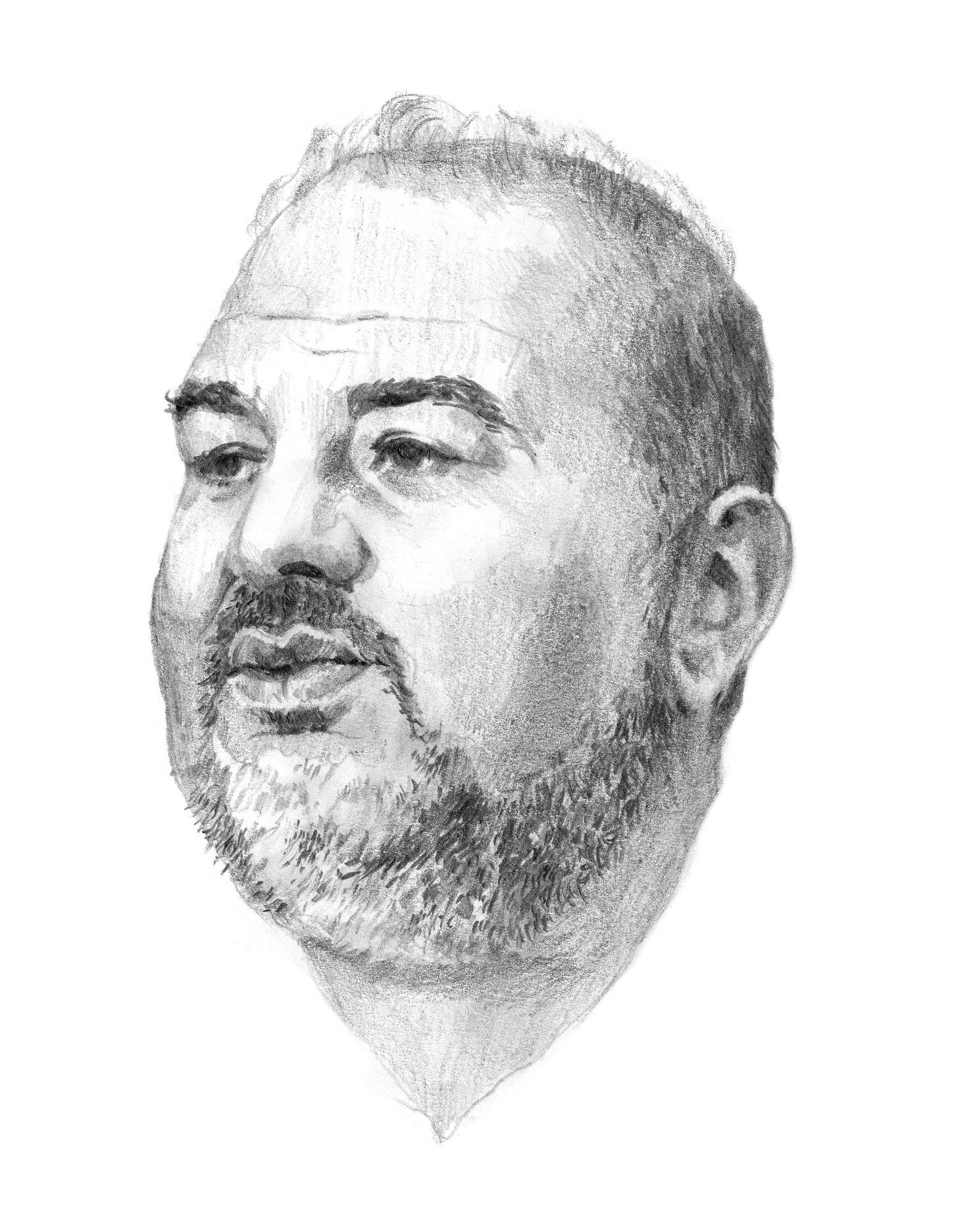

Yair Lapid, Drawing by Igor Tepikin

And having the opportunity to act as prime minister during this lame duck period confers significant advantage on Lapid. It is he who represents Israel internationally, which he manages quite deftly. In addition to the mid-July visit of President Biden and his handling of the recent rocket attacks on Israel by Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Lapid also teamed up with President Biden to issue a sharply worded condemnation of Iranian leadership for encouraging, if not ordering, the attempted murder of Salman Rushdie recently in Chautauqua, New York. Every one of these limelight moments must irk Netanyahu. Lapid, in terms of bloc leadership, is his main competition. And each one of these marquee moments if handled well, enhances his electoral chances.

NATIONAL UNITY

(Formerly Blue and White-New Hope)

Knesset #24 – Blue and White – 8 seats

Knesset #24 – New Hope – 4 seats

Currently polling at 12-13 as National Unity

Since entering the political ring in 2018, General and former IDF Chief of Staff Benny Gantz has gone from bust to boom and then all over again. Leading the Blue and White ticket in 2019 with Lapid taking second spot, and Moshe Ya’alon and Gabi Ashkenazi filling out the front bench, Gantz’s political naivete led to many novice scrapes and burns. His party fell apart. Bibi ran circles around him in coalition negotiations and at the Cabinet table and Gantz, for a while, was painful to watch. Like, you just felt sorry for the guy.

In the runup to election #4, many discounted his political future, questioning if he would cross the threshold. Not only did he do that, but he came through with an astonishing eight mandates. Since then, his polish and steady temperament has served him in good stead. Benny Gantz won’t set the world on fire, but he’ll stare ahead and walk in a straight line.

As discussed in our Election Guide for the Right, the merger for Election 5 of Gideon Sa’ar’s New Hope party with Gantz’s Blue and White was mutually beneficial. Sa’ar conferred right-wing and leadership credibility on Gantz. In return, Gantz offered Sa’ar a real chance of surviving to cross the threshold. But with the recent addition to the team of General Gadi Eizenkot, who is considered to be left of Benny, Sa’ar is going to be pressured to demonstrate to his constituents that he isn’t going to be pulled to the center or, worse, the dreaded left.

Drawing by Ioan Szabo

Gantz's big scoop in getting General Gadi Eisenkot (announced two weeks ago), a popular retired IDF chief of staff, to join Blue and White turned heads. Eisenkot was courted by Lapid – and likely others – but he bet on Benny. The Israeli electorate has always favored former chiefs of staff in national politics. Every government needs a good, strong, experienced military person to manage the incessant security challenges.

It was expected that Eisenkot’s announcement would give a lift to whichever party he joined but that did not materialize. Typically, there is a significant spike “in the moment” that tapers off. In this case the anticipated spike was more like a little bump.

In terms of policy, the trio seems to be solidifying a position that they will not sit with a Netanyahu-led coalition but otherwise, all bets are on.

LABOR

Knesset #24 – 7; currently polling at 5-6

The party of Israel’s founding generation, socialist Labor, has fallen on hard times. Its fortunes have consistently been on the decline – with a few blips here and there – since Rabin’s assassination. In each of the last four elections there has been deep concern as to whether the party would cross the Knesset threshold, and certain contests have been distressingly tight for Labor.

Traditional Labor is the bastion of an aging and shrinking demographic – primarily kibbutz and union-based. And as the pie has gotten smaller the vicious backbiting has intensified, leaving sorry remains of the party’s former glory.

Since 2021, Merav Michaeli, a 50-something Tel Avivian, has helmed Labor and is credited for her spirited efforts to rebuild the party and restore a measure of its former glory. In Knesset #24 Michaeli served as Minister of Transportation, with mixed reviews. She swanned through a recent leadership vote (they call them “primaries” in Labor and Likud) to maintain the top spot.

But many of her colleagues dropped well down on the Labor list, among them, Nachman Shai, considered a national icon by many. During the Gulf War in 1991 it was Shai’s calming, clear voice that reassured the nation as Scud missiles from Iraq hammered Tel Aviv, Ramat Gan and other areas of Israel. The top names on the Labor list are much less familiar to the general public – which may be a good sign that the party is undergoing a true refresh with a newer generation of politicos.

Nevertheless, Labor is polling at the same number of seats as were won in the last election. Michaeli has a reputation for being more than a touch haughty and the poster girl for the stereotypical Tel Avivian: upper middle class, well-educated, pronoun-conscious, and decidedly not religiously observant. She will have to broaden the party’s appeal and attract a wider support base to ensure a meaningful future for the party.

To that end, Michaeli has been telegraphing her openness, having recently attended the wedding of the granddaughter of Moshe Gafni, leader of United Torah Judaism. There she was, holding hands with the bride and dancing at the gender-segregated celebration in the hardcore Haredi city of Bnei Brak. As for sitting in a Bibi-led coalition? It seems that’s the one Rubicon she will not cross.

MERETZ

Knesset #24 – 6 seats; currently polling at 4

Meretz in its current iteration has been around since 1992 and represents a slightly harder left than Labor, in theory. The party self-describes as being social-democratic, focused on social and economic equity and favoring a two-state solution to the conflict. Its most recent leader, Nitzan Horowitz, performed reasonably well as Health Minister in the last Knesset but was reported to be an abject failure in terms of managing his small caucus and relations with other parties in the governing coalition. Reading the zeitgeist he stepped down from the top spot, likely sparing himself and the party an ugly battle.

Just elected last night in party primaries to lead Meretz in this election is former leader Zehava Galon. The stakes in Election #5 are potentially existential for Meretz, which is why she came out of retirement to take the reins at this critical juncture. From 2012 to 2018 she led Meretz and is quite roundly admired for her political and interpersonal skill. She has been drawn from retirement by a very real possibility that Meretz may not cross the threshold and hopes to buttress the party for a less precarious future. As can happen after an absence of several years, any shortcomings of Galon have been forgotten and she all but walks on water in the eyes of potential Meretz voters.

RA’AM

Knesset #24 – 4 seats; currently polling at 4-5

Mansour Abbas is a very skilled politician leading this Islamist party, and spoke recently to State of Tel Aviv, which you can read here. In the last election, Abbas demonstrated prescience and courage when he took his party from the cluster of “Arab” parties running under the umbrella of the Joint List, believing that he could cross the threshold and wield real power in a coalition government, no matter who governed.

He was right. For the first time ever, an Arab party was officially supporting a governing coalition. His focus was on promoting policies to address concerns specific to Israeli-Arab communities: high crime rates; policing deficits; inferior infrastructure; quality education and a quite dire housing crunch. His independence has earned him many enemies among the Arab communities and has provided perfect fodder for many right-wingers to stoke fear among Israelis; with the latter branding Abbas a trojan horse conniving to subvert the country from within the system.

Mansour Abbas, Drawing by Igor Tepikin

Abbas dismisses such allegations with a shrug. He has openly stated that Israel is a Jewish state and will remain so and that his mandate is to advocate on behalf of matters of particular concern to Israeli Arabs. He commented recently that he has much more in common with the ultra-orthodox than secular Jews, being a man of faith, meaning that he is also quite conservative with respect to social policy. So, branding him “left-wing” is pretty absurd.

Likud is busy these days painting Lapid et al as leftists who are creating conditions for Arab Israelis to incrementally take control of the state. It’s a ridiculous claim for many reasons. And then there’s the irony of the fact that Bibi also tried to convince Abbas to support a Likud-led coalition in the past. Today, Abbas and others bring this up often, but Bibi and Likud say, “it never happened.”

How Abbas parlays his new status in the next round of coalition negotiations will be important to watch. No predictions here. He could well be a key player again.

JOINT LIST

Knesset #24 – 6 seats; currently polling at 5-6

Drawing by Ioan Szabo

Four small parties coalesced under the “Joint List” umbrella in 2015 in order to ensure that they crossed the threshold to sit in the Knesset. It’s an alliance in name only, bringing together quite diverse ideological groups. These parties are solidly made up of Arab Israelis with a Jewish candidate included very rarely. They tend to be left-leaning and anti-Zionist, making their participation in the national government paradoxical, to say the least. In the Knesset their presence is largely disruptive and controversial.

Even among their natural constituency, Arab Israelis, Joint List party leaders have little traction, reflecting a high degree of alienation. The Arab vote in recent elections has been low by historical standards, indicating a lack of interest in the process and outcome. If the Joint List was, however, able to get out the vote more effectively, it would alter the deadlock of other parties significantly, making for unforeseen governing coalition possibilities.

ETCETERAS

More than 30 parties are typically on the final list at elections. As everywhere, there are crank attention seekers, but there are always a few very capable political players who for various reasons strike out on their own, thinking that they will break through the threshold. It’s often a losing slog. And every so often there’s a great story of the one that achieves the near impossible for a new party.

VI. BOTTOM LINE

It’s all about the numbers and who can negotiate a coalition government with at least 61 of 120 Knesset members. The post-election process can drag on for months. Following E-Day, each party leader has an audience with the President (and former Labor leader), Isaac Herzog, to express their support for one of the larger parties to form a governing coalition. Once tapped, the chosen party has a month, give or take (there are rules that can be applied to extend the time in specific circumstances), to return with a solid proposal.[2]

If they fail then the opportunity to form a coalition is granted to another party or, if the President determines that such a move would be fruitless, new elections may be ordered.

Israel is facing Election #5 because in the last four there have been deadlocks, with unstable coalitions squeezed in every way until they collapse. The electoral numbers look no different this time, which is a cause for serious concern. If the deadlock continues then Israel may well be forced to consider major electoral reform, the most likely approach being the limitation of the number of parties permitted to run.

This juggernaut distills to a few key issues: Who will sit with whom and who will not, being a big one, driven primarily by the “Anyone But Bibi” camp. Leading that group are Lieberman’s Yisrael Beitenu and, for now, Benny Gantz’s National Unity party.

The Haredi parties say they will never sit with Lieberman or Lapid’s Yesh Atid but I wouldn’t put money on that sticking. The Haredim have rarely been shut out of government as they were for the last year and a continuation of that situation is existential for them. They absolutely need power and influence to maintain control over their communities and there is no better way to do that than by having power in government.

Most significantly, however, is that the complexion of the next government will profoundly influence the direction that Israel takes in the coming decades. Should a strong right-wing coalition be formed, with Haredi support, the Center and Left will warn that it is no exaggeration to posit that Israel will trend towards “theocracy-lite” and away from democratic ideals.

And the right-wing bloc will assert the opposite: that should the Center and Left succeed then the state will lose its Jewish character and, consequently, the foundational reason for the existence of a sovereign modern Israel.

The stakes are very high.

Editor's Notes

1) The term “yishuv” refers to the areas of Jewish settlement in the Ottoman era and under British rule in Mandatory Palestine leading to the creation of Israel in 1948.

2) Following an election in Israel there is a logical assumption by many that the party with the largest number of seats will be tapped by the President to form a governing coalition first. Although that is often the result it is not always, as the mandate is delegated to whichever Knesset member has the best chance to form a majority coalition. Among the anomalous instances where the party with the most seats was not asked to form a governing coalition was in 2009. Tzipi Livni’s Kadima party took 28 mandates compared to Likud’s 27. Following all the conferences, however, Likud was tasked to negotiate a coalition after the President believed Likud had the best chance at forming a government, based on his deliberations with the parties.