Hungary’s Uneasy Peace With Its Fascist Past, in the Present

Vivian Bercovici travels to Budapest to explore Hungary’s uneasy relationship with its fascist past and how local Jews are navigating its resurgence

I.

Balasz surprised me with his excellent, unaccented English and old-world manners. As he drove to my hotel from Budapest’s Ferenc Liszt airport, I asked him to point out any interesting sites, in spite of the late hour and darkness.

Knowing I had arrived on an El Al flight from Tel Aviv, he chose to take the conversation elsewhere, commenting on how unhappy people are in Hungary. “Well, not quite unhappy,” he struggled with his somewhat limited range of expression, “but frustrated.”

“With what?” I asked, genuinely curious.

In his early 20s, Balasz studies finance and Russian language at university and drives a taxi for extra income. From ages 6 to 12 he lived with his family in South Florida, but they were unable to secure green cards and returned to Hungary, very disappointedly.

But, that was then, he said. Balasz wanted to talk about the present and how “some people keep bringing up the past. These things happened 70 or 80 years ago. The same people who did that are no longer alive. You can’t burden the young and the future with the past.”

He had clearly paid attention to the fact that I had arrived from Israel, assumed that I am Jewish and surmised that I may be interested in the issue of Hungarian collusion with the Nazis during WWII. He was correct on all counts.

A touch unnerved by his boldness, I engaged cautiously, suggesting that what mattered more than the passage of time was what Hungarians truly believed and thought of others. Today. Anodyne enough, I thought.

Neither one of us said out loud what we were really talking about: the enthusiastic participation of many ethnic Hungarians in the mass slaughter of more than 500,000 Jewish citizens during WWII.

II.

Until recently, Balasz had lived in a small, rural town with his family. According to an Anti-Defamation League survey taken in 2019, 42% of Hungary’s 10 million people hold antisemitic views, among the highest measure in eastern Europe, which comes in at 34% overall.

Approximately one fifth of the Hungarian populace today lives in Budapest, considered to be a liberal stronghold. This means that outside of Budapest antisemitism is very prevalent, much more so than in the capital.

As a local acquaintance commented to me the day after my arrival, Balasz is “one of them”; a supporter of Viktor Orban, leader of the majority Fidesz party. Or, perhaps, he’s a Jobbik man – the openly and virulently antisemitic party supported by 20% of the Hungarian electorate.

Orban has been a fixture in post-communist Hungarian politics from day one, evolving from a right-of-center classical liberal to a self-described illiberal autocrat. He has served as prime minister for the past 12 years consecutively and throughout that time Orban has diligently galvanized the support of the vast majority of Hungarians by appealing to ethnic nationalism tinged with a distinctly Jew-hating bent.

In fact, during Netanyahu’s previous term in office, his reputedly close relationship with Orban – among other autocratically inclined leaders – attracted significant attention and criticism. Israelis were and remain divided: Is it incumbent upon Israel to adhere to a “moral” foreign policy, due to its mass trauma? Or, as the counterpoint view would posit, is Israel just another one of many nations with a duty to its citizens to manage a hard-nosed, realpolitik-based foreign policy that promotes its national interest?

Should Bibi succeed in forming his hard-right government in the coming days, as expected, the Orban issue will surely pop up again. And soon.

III.

In 1939, there were 850,000 Jews among the population of 9.1 million Hungarians. In urban areas, they tended to be assimilated and successful. In Budapest – referred to as “Jewdapest” by some – Jewish Hungarians comprised 25% of the city’s population.

By the end of the war, more than half – approximately 530,000 – had been murdered. The majority of those who survived were Budapest residents, able to avoid detection and roundups due to their integration with the broader society. In a small village, though, where everyone knew everyone, there was nowhere to hide.

Within eight weeks, from the end of May through July 1944, approximately 450,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz, where most were murdered upon arrival. Enthusiastically preparing for this unprecedented pace of slaughter, Adolf Eichmann – recognized as having been the architect of the notorious “Final Solution” – was headquartered at Budapest’s Astoria Hotel from March through August, overseeing the ambitious plans. He scorned his Hungarian deputies for aspiring to deport 20,000 Jews daily, considering that to be an absurdly high number. Eichmann, it is reported, considered 5-6,000 daily to be an ambitious quota. In the end, the actual number fluctuated, at times soaring to 12,000. In a single day.

We know now that the killing machine of Auschwitz was overwhelmed by the Hungarian influx, resulting in the journey of the doomed taking a little longer than it might have. Trains moved along slowly, halting for long periods during the journey, sealed in cattle cars. They had to wait for the unloading “ramp” to be cleared of the new arrivals which overwhelmed even Auschwitz.

Most of the photos we have – and they are precious few – of new arrivals being “sorted” for slave labor or immediate slaughter – are of Hungarian transports. On one particular day, which happened to be sunny and beautiful, a Nazi photographer memorialized women and children sitting in the grass nearby the gas chambers, waiting for the backlog to be “processed.”

IV.

Hungary is home to quite a large Jewish community – particularly for post-war Central or Eastern Europe – numbering about 100,000. Almost all live in Budapest. Throughout the communist years this ravaged community kept a low profile, but a gradual awakening has revived all aspects of Jewish communal life in the last thirty years, in large part due to foreign philanthropy.

But with the confidence come risks. As Orban’s nativist support spreads and deepens, it is the Jews who are suspect and targeted. As have many other European leaders in past decades, Orban promotes a historical narrative that presents Hungarians as having been innocent bystanders when the Jews were designated enemies of civilization, taken from their homes and shipped off to be murdered. The fact that ethnic Hungarians required no encouragement to turn over their Jewish compatriots to the local fascists – and then loot and steal their property – is conveniently overlooked in the Orban era.

Eight years ago, a monument was erected in Budapest’s “Freedom Square” in the middle of the night. The sculpture was, ostensibly, meant to commemorate the 70thanniversary of the mass deportation of Hungary’s Jews. However, Jewish community representatives were not consulted in the design, which turned out to be highly controversial. Reinforcing the preferred national myth of innocence, the statue depicts a German eagle pouncing on the Archangel Gabriel, a clear metaphor of evil prevailing over good. This installation has, understandably, riled the Jewish community, among others.

The historical revisionism favored by Orban’s Fidesz members and their Jobbik party allies received a very public affirmation with the installation of this statue. Their preferred version of history, which is factually untrue, is that ethnic Hungarians had no part in the deportation and murder of its Jews.

But it is a well-known fact that the Arrow Cross – local Hungarian Nazis – were often more ruthless than the Germans. They, and many local citizens, needed no encouragement to torment and loot and kill Jews.

And this is exactly the sort of talk that drives Balasz, and many Hungarians, crazy.

My Budapest acquaintance, whose adult daughter converted to Judaism to marry, tells me that she worries. A lot. She sees a significant spike in antisemitism in Hungary. Her daughter recently left the country with her young family, and she wonders how many others will follow.

V.

Orban has been criticized for his propensity to indulge in antisemitic dog whistles, particularly when it comes to billionaire philanthropist and Hungarian-born Jew, George Soros. Ironically, Orban briefly attended Oxford University in the late 80s on a Soros-funded scholarship. These days he openly maligns Soros as a subversive activist bent on some sort of nefarious plan to control and undermine Hungary.

Classic European antisemitism that resonates with the masses. There is a threat. “They” want to undermine our culture and great nation. Again.

The Jews.

Orban’s Fidesz party controls more than 50% of Parliament, with Jobbik and other smaller political allies bulking up the hard-right control. This leaves an anemic opposition that is concentrated electorally in Budapest. They are increasingly marginalized politically and, of course, by the state-controlled media that dominates nationally.

Control of Parliament and the media ensures that Orban’s preferred narrative dominates. Even so, he seems somewhat sensitive to criticism, particularly when it comes to the Jewish Question.

Hence, “Operation Statue” at 2 am. Orban’s people were concerned that if it was installed during the day that there would be protests, cameras and unwanted publicity. The stealth solution took care of a lot of the potential messiness.

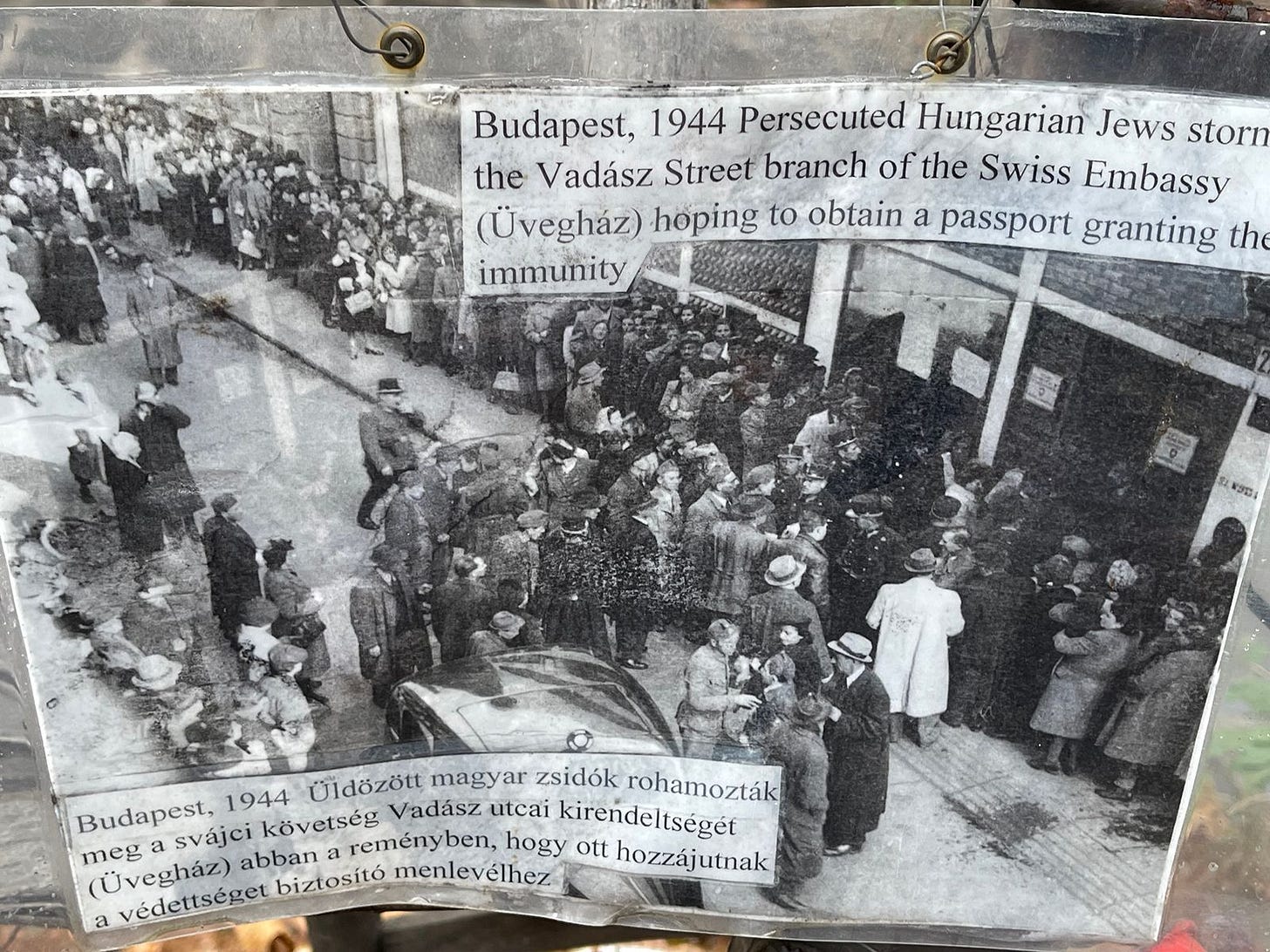

Ever since, a silent protest at the site has been ongoing. Home-printed signs and messages record and present the photos and facts of so many Jewish Hungarians who were murdered. They are silent but profound testimonials: This did not happen in a vacuum. It was not the Germans who did this. It was local Hungarians.

Every so often the leaflets are cleared away and soon replaced. Virtually all of the protesting notes report on Jewish lives lost and remind the public that the families and friends of the deceased remember. The truth will neither be eradicated nor whitewashed.

For various reasons, the mass deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz was temporarily suspended for a few months at the end of July 1944. It never resumed its original frenzied pace. This had everything to do with the advancing Red Army which led to a shakeup in local Hungarian leadership. But the fascist enthusiasm to kill every last Jew never waned.

In the interim, local Hungarian thugs would capture unlucky Jews. Some were in hiding, some out foraging for life necessities. Some were returning from smaller work camps in Austria, where the jailers and overseers could see the war’s end coming. The Nazis were keen to escape the wrath of the conquering Soviet army. So they abandoned their posts and quietly went home. Pockets of forced laborers suddenly found themselves free. Many were Hungarian and made their way back to Budapest.

Most of those snared by the Arrow Cross fascists were taken to the banks of the Danube River, which bisects modern Budapest. Two people would be tied together at the ankles to save bullets. One shot ensured that they both fell into the frigid waters, with the second person suffering a slower, more agonizing death. Today, many pairs of bronze cast shoes, said to be true replicas of those worn by Danube victims, are affixed to a small area on the river promenade, another powerful reminder of the past, which Balasz would prefer to erase.

A familiar sense of alarm imbues the Hungarian Jewish community presently. Query the degree to which it ever really dissipated. In spite of the foreboding signals, its members identify strongly and foremost as Hungarian. As so many Jews believed in the years leading to 1944, that they were as Hungarian as anyone.