From the Desk of TelaVivian, Vol. 3: On the Kotel and 1967

Our Founder/Editor-in-Chief gets personal about the meaning of 1967 and Judaism's holiest site

By Vivian Bercovici

It is impossible to speak about Israel and the Jewish people without addressing “the Kotel.”

Also known as: The Western Wall. The Wailing Wall.

Vivian Bercovici, Drawing by Igor Tepikin

We all carry an image of it in our heads. For many Jews of my vintage, it will be an old sepia-tone photograph or mid-century illustration in a worn Passover Haggadah. Dusted off annually for the Passover Seder meal, the Haggadah structures the ritual retelling of the story of Jewish liberation from slavery in Egypt and redemption in the Kingdom of Israel.

For others, their “go-to” image of the Kotel may be a photo of a celebrity reverently touching the massive stones, surrounded by beefy security, photographers and assorted political types. All heads of state and rock stars – the most recent being Maroon 5’s front man, Adam Levine – visit the Wall when in Israel. To skip it would be like touring the Vatican and not stopping in at the Basilica or the Sistine Chapel. It's just not done.

I. 1967

Fifteen years ago, when I first brought my daughters to Israel, they were aged 10 and 14. In Toronto they had attended a Reform Jewish day school, so they had some knowledge of the significance of the place. Real life was something different altogether.

One Friday in August 2007, around 5 pm, we walked to the Kotel Plaza, a vast area with an imposing, stone wall being the focus.

I grew up hearing about the Jewish yearning – for more than 2,000 years – to pray at the “Wailing Wall,” as it was referred to in our community. I also knew that since the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, Jews had been banned from worshipping there. [1]

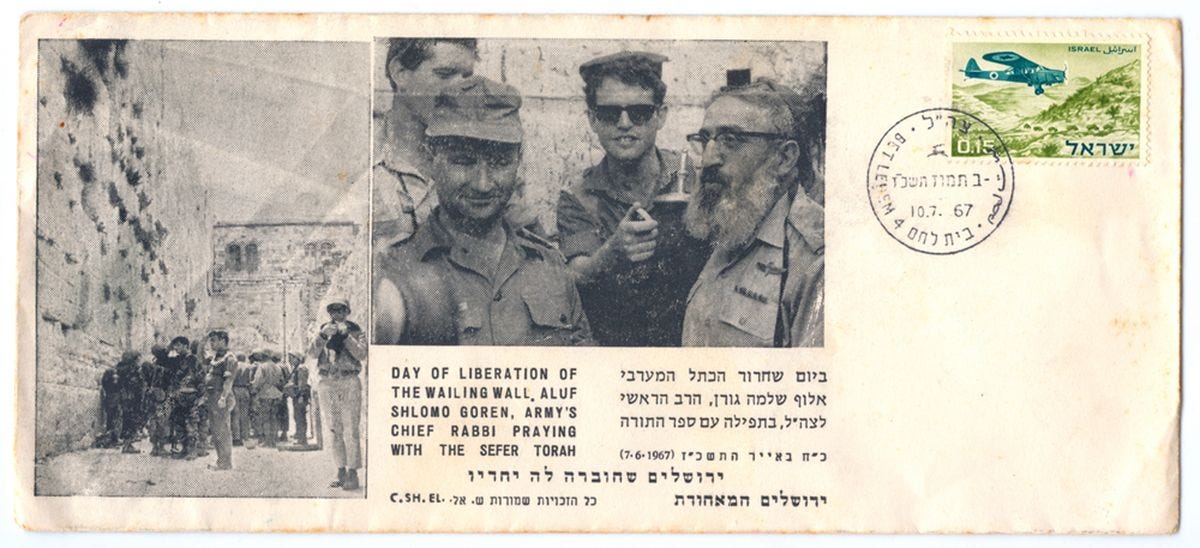

All that changed in June 1967, when the Israeli army achieved an extraordinary victory, overcoming the combined military forces of Syria, Jordan and Egypt. The Six-Day War, as it is known, ended with Israel controlling three times the territory that it had a week prior.

Israelis were euphoric. They felt invincible. One day they had faced annihilation; the next they were triumphant. What shook the Jewish world to its core, however, was that Israeli warriors had reclaimed the Kotel, and Jerusalem, the eternal capital of this ancient nation, reborn.

For me, 1967 was a big year. It was the Centennial celebration of Canadian sovereignty and we learned a bunch of fun songs in school to prepare for the endless firework extravaganzas. New parks, pools and libraries were built. The Keynesian spendthrift era was in full swing.

It was also the year that the Nigerian civil war broke out, with heartrending photos of starving Biafran children on the front pages of western newspapers. As a six-year-old child, I was gutted, seeing so much of the past in their swollen bellies and sunken eyes. As comfortable as my life may have appeared, beneath the surface I churned. A mere 16 years before I was born, Jewish babies were being slaughtered with unimaginable savagery in Europe. Nothing about the Holocaust was abstract for me. Nor was Biafra. Not even at age six.

The north Toronto suburb where I lived as a child was overwhelmingly Jewish. It was also heavily populated by Holocaust survivors. Numbered forearms were everywhere. We kids knew about the camps, by name, and which of the “jobs” in these infernos meant the slimmest possibility of survival. We understood, viscerally, that we lived in place of so many who had perished.

We were keenly aware of the constant torment that plagued survivors, and that we absorbed, by osmosis. How could we truly enjoy our life when six million could not? Their collective bequest to us, the survivors and their children, was an enormous responsibility to remember and ensure that their torment was not in vain.

This complex psychological manifestation is often referred to as “survivor’s guilt.”

In case we forgot, we were reminded, constantly and explicitly of our destiny. Our existence, we were told, was the best revenge on Hitler.

The mother tongue of more than 50% of the adult residents of our neighborhood was Yiddish. Many were poorly educated (due to the war) and almost all had bad teeth. The local dentist took care of the oral issues and the education thing took care of itself. It was understood. Our main job, as kids, was to excel. Keep your head down. Don’t draw attention to yourself. Eat what is on your plate and never complain. Ever. Because you have no idea what it is to go hungry, to be fearful, to lose.

“A bad day,” my father once said to me, when I thought I had had a terrible one, “is thinking that you may be on the next train to Auschwitz.”

We intuited behavioral appropriateness. In those days, there were no therapists, and society was insufficiently equipped to deal with any feelings, let alone the intergenerational transference of extreme genocidal trauma.

Our parents were shunned by the established Jewish community, as were their children.

Truth is, that part’s not all bad. It was a bit too Darwinian at times, but we learned how to manage our lives. Teams won and lost. People came in first, second and third. Not everyone got a prize. And some teachers were downright mean. Even antisemitic.

But we also knew how much worse it could be. We understood not to ask about certain things. Like, what our parents did for fun when they were children. At school. In the summers. Their favorite foods when they were kids. Everything was taboo.

These were the days when the prevailing wisdom was that six million Jews went to the slaughter like lambs, with no resistance. The level of ignorance and heartlessness entrenched in Jewish communities was staggering. In the broader population it was worse. There was neither compassion nor empathy.

We did not have extended families. Our parents were shunned by the established Jewish community, as were their children. We were different. The survivors understood that they were to bury their grief, sublimate their shame, and do their utmost to forge on and live some semblance of a “normal” life.

“It” was simply not to be discussed. Which explains why they overwhelmingly married other survivors. (My parents were an exception. My mother was born in Canada.) And why their social circles were often closed systems of their exclusive group. No “outsider” could possibly understand.

How many times have you heard about a survivor, speaking in recent years to schoolchildren, who said they had never uttered a word about their experiences until recently? Or that they never discussed their hellish pasts, even with their own children?

They, the survivors, should have been honored in their communities.

There is no “normal” for a survivor, or for the children of a survivor. In fact, we now know that the psychological impact of the trauma on successive generations can be more pronounced due to behavioral genetic responses. But, I’ll leave that issue to the neuroscientists to address.

Back to the Six-Day War in 1967.

When it broke out, the tension in my family home was indescribable. “Normal” life was suspended. And then, as abruptly as it had set in, it disappeared. We could breathe, again. Play. Ride our bikes. Even laugh. We ate dinner as a family again, however dysfunctional. We were no longer hovering between life and death.

We were told, over and over, that if Israel was defeated there would be another Holocaust. As my father used to say: “Don’t tell me it can’t happen again. Because it did happen.”

II. The Kotel in all its Glory

For me, the Kotel was pure majesty. In the mythic reality of my mind, it represented life. Tenacity. Belief. Soul. I was never a religiously observant person, but it was as spiritual and moving as a place could be. It affirmed Jewish nationhood, peoplehood, identity, existence, hope. And, most recently, power.

That evening in August 2007, my girls and I, we didn’t really have a plan. I hadn’t thought through the Kotel visit. I just assumed it would cast its spell – as it had done to me 30 years earlier when I first visited Israel – and that would be that. But things didn’t work out as I’d thought they might.

Nearing the end of our time there, one of my girls asked me: “Why is there so much less prayer space for the women than the men? And why are the boys allowed on the women’s side with their moms, but the girls aren’t allowed on the men’s side with their dads?”

It was broiling hot, and the sun was still strong in the late afternoon. We found a shaded patch on the steps leading to the plaza, our home perch for the next three-plus hours. One of us always held down the fort while the other two wandered off to explore, now and then.

When we arrived, there were very few people in the sprawling Kotel plaza. By the time we left, close to 8:30 pm, it was jammed with a diverse mix of the pious and the curious.

We sat for hours, watching tourists and locals come and go; observing the different sects of Hasidic men stream through the plaza entrance, decked out in their Shabbat finery. Whereas I am no expert in the sartorial nomenclature of the ultra-orthodox, I did know enough to explain to my girls the significance of the various costumes worn so proudly in the withering heat, which were much more suited to the climate of the Pale of Settlement, where they originated. [2]

The Kotel plaza transformed, in slow motion, from empty to teeming, a mélange of the familiar and less so.

We saw a woman who had been at the Office Depot in Toronto a few weeks earlier, with six kids, getting a head-start on school supply shopping, as were we. In Toronto, she stood out, with her head covering and unusually large family.

At the Kotel, she blended into the crowd.

“OMG. Mommy! That’s her!”

It was a moment of worlds colliding on so many levels and demonstrating the powerful ties of all Jews, secular, traditional and religious, to this place. The Kotel.

Nearing the end of our time there, one of my girls asked me: “Why is there so much less prayer space for the women than the men? And why are the boys allowed on the women’s side with their moms, but the girls aren’t allowed on the men’s side with their dads?”

As I had told my daughters when we arrived in Israel, this country does two things well: teaches Hebrew to newcomers and manages security issues. The rest, I said, is hit and miss.

My responses were careful, explaining that the Kotel was managed according to the customs of the ultra-Orthodox, which required gender segregation (with the exception of young boys), and recognized the more central role of prayer and ablution in the lives of men. With respect to the smaller space allocated to women, the textbook explanation (from an orthodox perspective) is that men are less innately spiritual than women, and therefore ritual devotion is necessary to help them to feel closer to God. So, more men attend and therefore they need more room.

Hey. I didn’t say that is my view. But I did work hard to provide my kids with as neutral and historically accurate a rendering as possible regarding the wisdom of the Kotel overlords. Deference aside, I minced no words in letting them know what I thought about this centuries-old patriarchy, more focused on control than spirituality.

And, so, we lingered, soaking up the scene, amidst this babel of sound and language. There was so much contrast, between the uber-pious focused on their higher power and the many voyeurs, like us, who had come to watch this ancient place come alive.

At one point, my older daughter looked at me and said: “Is this it?”

I wanted to scream.

“Is this it?!?!? Do you understand the passion, desperation, hope, yearning that has been projected onto this place for millennia?!?!? IS THIS IT?!?!?”

But patient Viv stepped in and saved me from myself.

I paused. I looked around. I reflected. And I was as surprised as anyone to hear what I said next.

I explained that this was HQ for the Jewish people. But, unlike the Vatican, or Westminster Abbey – two Christian houses of worship that western culture understands – there was no central figure coordinating any ceremony at the Kotel; no ornate pulpit or gilded pews. No artwork adorned the surroundings. Just the ancient remains of a former glory.

Furthermore, each individual from this famously self-described “stiff-necked” people was, in prayer, his or her own boss. They did what they knew to be the right thing. All that was important in this place, in theory, was the personal connection of the individual to God; an intensely private and intimate matter.

The tableau before us was a work very much in progress: the ingathering of the exiles following a 2,500-plus year Diaspora. It was organized chaos, much like Jewish life.

As I had told my daughters when we arrived in Israel, this country does two things well: teaches Hebrew to newcomers and manages security issues. The rest, I said, is hit and miss. (I am delighted to report that things have improved considerably on that score since 2007.)

III. Modern Jewish Reality and Kotel Tradition

Our Kotel outing occurred before the issue of egalitarian worship became the Big Thing it is today on the Jewish issue matrix. The cause has, in recent years, been driven largely by an Israeli activist organization, Women of the Wall, which has been advocating for egalitarian prayer at the Kotel since 1988. Today, they are supported by many liberal Jewish groups with power bases primarily in America, accounting for the much higher profile accorded the matter.

The status quo, however, has not changed and I wager that it will not any time soon.

Helping to parse this seemingly intractable conflict, this week we have two titans of Jewish thought and action, weighing in on this issue. Former Prisoner of Conscience in the USSR, Natan Sharansky, and acclaimed historian, Professor Gil Troy, will bring their passion, deep knowledge and surgical analysis to the “backstory” of the Kotel compromise – which was meant to address so many of the same questions my daughters were asking in 2007 as well as the ongoing issues championed by Women of the Wall and others.

After years of painstaking negotiation, an agreement of sorts was reached by various “authorities” – coordinated by Sharansky – as to how to manage Kotel protocols and practice. This compromise ensured that everyone was dissatisfied, meaning that it was probably a good one.

But, it withered and died. The Kotel compromise was never implemented.

The upcoming Sharansky-Troy telling of this story that we will publish next week is a “must read.” The Kotel controversy is, in so many ways, a metaphor for the larger social and political fragmentation that can be so destabilizing – and maddening – in Israel. The tension is between sclerotic and dynamic; ascetic and sensual; hidebound and adaptable; ancient and modern. At its essence, the quagmire today is no different from that which has always divided the Jewish people: the separation of religion and state and how, exactly, that should be balanced and managed.

IV. What’s Next

And now, the moment of truth: it falls to me to inform you that State of Tel Aviv will be putting in place a paywall on the Sharansky-Troy piece and more of what we publish going forward. We will continue to offer enriching content to non-paying subscribers interested in our offerings.

It is important for all to be able to access and enjoy State of Tel Aviv in some manner – but we will differentiate by offering premium content to paying subscribers.

Why? Because we are investing significant resources to provide top-quality, well-written, superbly insightful essays. State of Tel Aviv is deeply committed to continuing to offer the eclectic mix of topics and writers that we have introduced since launching in mid-May. Without subscription support from readers, however, we will be hard pressed to maintain this ambitious project and to grow.

And, yes, we have plans. For the launch of a podcast in the fall. And then some.

In my debut column I set out the reasons for creating this platform: to develop a truly pluralistic “town square” where serious people (with a sense of humor, of course) could turn for truly unique weekly digital content.

We are not a breaking news outlet and have no intention of becoming one. We are not beholden to any particular ideology or partisan interest. We are a publication that is working hard to cultivate and curate a diverse range of writers and talent culled from Israeli society; immigrants and native-born; people who actually live here and have a deeper level of understanding of the place.

Our purpose is to explain Israel to the world outside with the inside savvy of those who actually have skin in the game, so to speak. And we are confident that no mainstream or legacy media is doing what we aspire to.

On a personal note, I’m kind of getting off on being called a leftist one week and a right-winger the next. See. It’s not about me or my views. As editor, my role is to curate and present the perspectives of Israeli influencers, writers, politicians, businesspeople. (As a writer I permit myself the same latitude I do any writer.)

I want to keep the writing and topics eclectic. I want to surprise the reader – and myself – every week. If what you seek is a self-affirming echo chamber, this ain’t your place. If you do, however, like the idea of a pluralistic town square that may make you uncomfortable now and then, you will enjoy the offerings and find the platform enriching.

And on that note, I sign off, hopefully yours,

P.S. Did you hear? We’re having another election! I know… hard to believe!

If you enjoyed reading this article, please consider supporting our work by becoming a paid subscriber to State of Tel Aviv.

Editor's Notes

1) From 1948-1967 the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan controlled the area known as East Jerusalem, where the Al-Aqsa compound and the Kotel are located. During this period Jews were prohibited from praying at this holy site.

2) From 1791 to 1917, Jews living in a large part of eastern and central Europe were required to live within an area called the Pale of Settlement. Borders were somewhat fluid but included present-day Belarus, Lithuania, Moldova, large parts of Ukraine and Poland. Sections of other territories were also included in the Pale.

Life was difficult and poverty rampant. The surge of Jewish emigration to the United States and other western countries in the late 1800s and on was largely from the Pale. It was here – as well as in adjacent areas (among them parts of Romania and the Austro-Hungarian empire) that Hasidic Jewish sects flourished.

Each Hasidic group wore distinctive clothing, sometimes for religious reasons but clearly heavily influenced by the climate.

The “shtreimel,” a donut-shaped fur hat, is commonly worn on Shabbat, special holidays and festive occasions. Many sects have a signature style of shtreimel made with a particular fur and details that signal their tribal affiliation to “those in the know.”

Shtreimels were introduced in the Middle Ages in parts of northern Europe as a sort of dunce cap. Jews were required by law to wear the donut headgear or, in some places, a conical hat, a humiliating sign of separateness. For whatever reason, the custom has been embraced over the centuries, mutating into a revered, old-country tradition.

Then, there are the caftans and robes. Each Hasidic sect has a distinctive robe, with a sash or belt – and the odd tassel or adornment (but never ostentatious), some of silk, some of wool, all clearly not workday attire.

Lastly, there are those who tuck their pant legs into their socks, resembling court jesters. A bizarre holdover from life in the primitive shtetls of eastern Europe where men typically wore simple black suits, the “tuck in” prevented their pant legs from being ruined by the rough walking and road conditions. The fashion persists; an odd affectation in Israel, land of very light winters.

Hasidic Jews may adhere to all or none of these dressing traditions, but the shtreimel remains the most commonly adopted.