A New Diplomatic Era: 5 Days. 6 Countries. No Palestinians.

How a Middle East summit in Israel with four Arab countries was organized in five days without any Palestinians

Note From the Editor, Vivian Bercovici:

Throughout last fall and winter there was a flurry of meetings that had Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid popping around the Middle East and Europe.

The assumption at the time was that the focus for regional leaders was on an imminently nuclear Iran, a terrifying prospect in this part of the world.

But the real story is more about how these gatherings came to be rather than the meetings themselves. Attila Somfalvi weaves the narrative so seamlessly and transforms a story that is essentially about process into a riveting read.

He clearly has superb sources and access to the right people. More importantly, he has a sixth sense as to which nuggets to polish; which anecdotes will most effectively give us a glimpse of the very real and relatable relationships forming in these inner sanctums.

These meetings have totally re-calibrated security and political realities in the Middle East and will have major, ongoing impacts in the region.

Enjoy the journey you’re about to take with Attila. It’s an eye-opening and beautiful read.

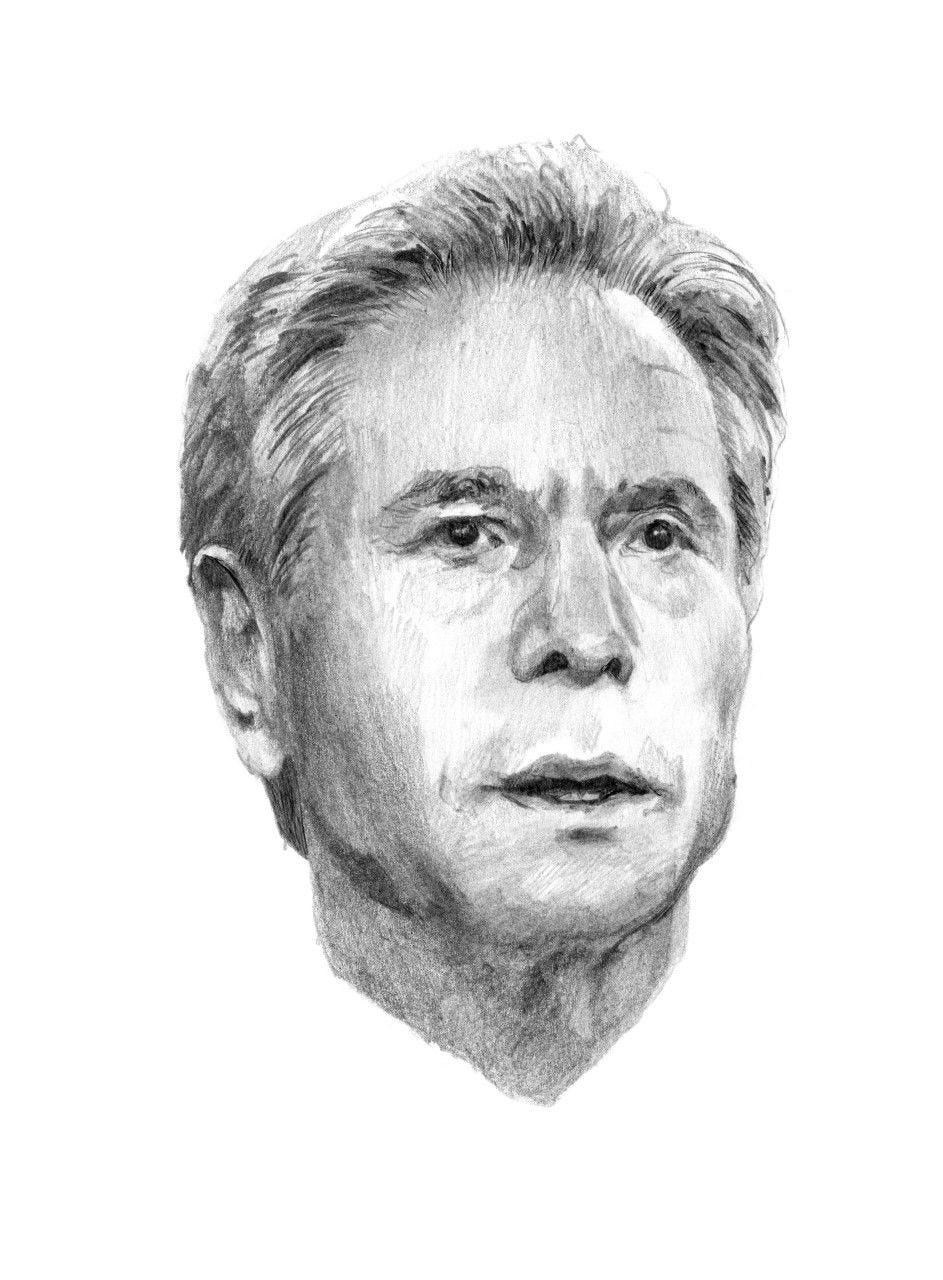

One sun-drenched afternoon in March, Israel's Foreign Minister, Yair Lapid, emerged from the front entrance of the luxurious Kedma Hotel in the northern Negev desert. A former television journalist, Lapid is known for his high energy and charisma. He also has a flair for drama.

Kedma Hotel is very near the gravesite of Israel’s founding prime minister, David Ben Gurion. Lapid chose that spot to host four Arab foreign ministers and the American Secretary of State, Antony Blinken. Sporting a black suit and open collared white shirt, he stood before the cameras, basking in the spotlight.

The choreography was brilliant, setting the stage for yet another iconic image to continue to define the Abraham Accords; a game-changing diplomatic agreement signed by Benjamin Netanyahu in the twilight of his term as prime minister.

Arab flags fluttering in the Israeli desert; an unimaginable prospect just two years ago.

In quick succession, an unprecedented group of foreign diplomats arrived to attend Lapid’s gathering, barreling along in their motorcades towards the hotel.

The limos pulled up, entourages disembarked, and Lapid stood there, beaming like a groom on his wedding day.

In spite of the festive atmosphere, there was one delegation missing: the Palestinians. Whether they were even invited was never confirmed, but an educated guess would be a strong “no.”

In preparation for the VIP arrivals, rows of flags of all attendees – the UAE, Morocco, Egypt, Bahrain, the United States and Israel – hung from every post. This lineup was unprecedented, and the international media were snapping photos from every possible angle.

Arab flags fluttering in the Israeli desert; an unimaginable prospect just two years ago.

I. Abraham Accords: Foundation of Change

As soon as the Abraham Accords were signed in August 2020 Israelis embraced the benefits that flowed. Tourists, businesspeople, political leaders, investors and entrepreneurs – or ordinary folk looking for a shot of glamour – rushed to visit the UAE. An astonishing 250,000 Israeli tourists flocked to the UAE in the first year after the signing. And this, remember, is after the onset of COVID.

This was a very different peace from that which had prevailed between Israel, Egypt and Jordan since 1979 and 1994, respectively, which were notoriously frigid relationships.

This was a peace between people; warm and seemingly genuine. Surprisingly, the Palestinians were a non-issue, their obstructionist approach to negotiation and compromise, over decades, having worn out the patience even of their Arab brethren.

The Foreign Ministry celebrated the rapid warming of ties, and Lapid began to dream of a regional construct that would bring together Jordan, Egypt and the signatory countries to the Abraham Accords.

Israelis reveled in a kind of euphoria, a sense that it might really be possible to dance at all the weddings: preserve – or just not deal with – the status quo in the West Bank and enjoy the benefits of regional peace.

By the summer of ‘21, the new Israeli “change” leadership had cobbled together a coalition by a whisker. It was a raucous mash-up of eight political parties, including those on the far right, the far left, an Arab Islamic party and everything in between. So ended, for now, the long reign of PM Netanyahu.

It was imperative for this impossible coalition representing quite divergent interests to find a way to notch some quick, high-profile achievements. In particular, key MKs felt pressure to demonstrate that they could be at least as impressive and competent in the foreign policy arena as was their great nemesis, Benjamin Netanyahu. His prodigious intellect and work ethic, combined with charm and flawless English, set a very high bar for these neophytes.

On his first day of office in the Foreign Ministry in Jerusalem, Lapid was briefed on the status of the Abraham Accords. Officials said that once the agreements were signed, everything had stopped. There had been no initiatives to build on the foundation blocks.

Pumped up with good intentions and a desire to demonstrate quick impact, Lapid understood that this was a significant opportunity requiring immediate action. For a start, it was critical to reach out to the signatory states; to demonstrate that Israel valued the new relationships and hoped to develop them.

Israelis can be an impatient lot, which Lapid understood well. As soon as the Abraham Accords were signed there was rampant speculation about “who’s next.” Saudi Arabia, for many reasons, was seen to be the crown jewel. If the Saudis entered into a formal peace with Israel, well, then, the Red Sea might just part, for an encore.

Accordingly, Lapid instructed ministry officials to work hard to imbue the existing Accords with real substance.

“In order that there will be another country that will come to sign,” Lapid instructed his staff, “the Abraham Accords must be a success story, with real diplomatic, social, economic and security value. We need to inject content into the Accords. In addition, there can be no difference between the older peace partners and those of the Abraham Accords. We need to build a coalition of all the states of peace.”

As a first step, Lapid decided to participate personally in the dedication ceremonies of Israeli embassies and government offices in Morocco and the Gulf states, as well as the official signing ceremonies for economic and business agreements.

That was the easy part.

The much more difficult part would be to defrost relations with the Egyptians and Jordanians. During Netanyahu’s time in office, he had so neglected relations with President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt and King Abdullah II of Jordan that bilateral relations with both countries – with the exception of security coordination – were in a deep freeze.

Israeli PM Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid understood that they had to address this deficiency and immediately set to work. Accordingly, Bennett’s first diplomatic meeting as prime minister was to meet with Jordanian King Abdullah.

The rendezvous at the King’s Amman palace was kept secret for about a week. At the end of June 2021, Bennett flew by helicopter to Amman to clear the air. He also came bearing gifts, of a sort, agreeing to sell 50 million cubic meters of water to its parched neighbor.

In September 2021, just two months after the relationship “reset” with King Abdullah, Bennett met with Egyptian President el-Sisi in Sharm El-Sheikh. This was followed up with a December visit of Yair Lapid to the Presidential Palace in Cairo.

“The Sharm Summit was an Egyptian initiative,” says an Israeli source who was involved in the summit. “This was the moment that the old peace, the cold peace, connected to the new peace, the warm one. It was a very, very important moment.”

The Foreign Ministry celebrated the rapid warming of ties, and Lapid began to dream of a regional construct that would bring together Jordan, Egypt and the signatory countries to the Abraham Accords.

In addition to the clear economic benefits, Lapid believed that a multilateral consensus among the majority of Middle Eastern countries would signal the emergence of a more formal regional security alliance against Iran. It might also have the added benefit of putting a damper on the Western keenness to renegotiate a “new” nuclear deal with Iran.

Read Attila Somfalvi's one-on-one interview with MK Mansour Abbas

II. The Warm-Up Act: Sharm El-Sheikh

In parallel to the efforts of the Foreign Ministry, the Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem was invested deeply in regional diplomacy.

It was clear that the Biden Administration was less than enthusiastic about validating the Accords, seen to be a Trump legacy. In fact, in the early days, key officials refused to even utter the term “Abraham Accords.”

No matter. Bennett and Lapid pushed on.

“Our challenge was to take the spirit of the Abraham Accords, the spirit of absolute normalization, and push it forward greatly,” an Israeli diplomatic source told me. “The path with the Emirates was incredible: The free-trade agreement was signed with lightning speed after the Prime Minister and MBZ (UAE's President, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed) agreed not to allow the negotiations between the states to get stuck.”

Furthermore, while still in the UAE, Bennett instructed the director-general of his office, Yair Pines, to receive the Emirati economic delegation in Israel for a week “at a nice hotel” to close the trade deal.

And, so it happened. Just like that.

The warmth and momentum between Israel and the UAE caught Egypt’s attention. President el-Sisi and Mohammed bin Zayed are personally close, and el-Sisi was included in many official functions. He was in on the action, liked what he saw and was looking for a way to benefit Egypt economically.

These rapid succession encounters warmed relations between the leaders, allowing for more natural interactions, and laying the foundation for the Sharm el-Sheikh Summit on March 22, 2022, a small but meaningful gathering which included Bennett, Bin Zayed and el-Sisi.

“The Sharm Summit was an Egyptian initiative,” says an Israeli source who was involved in the planning. “This was the moment that the old peace, the cold peace, connected to the new peace, the warm one. It was a very, very important moment.”

It was also at this time, as things were gelling regionally, that the Biden Administration began to emit confusing signals. Among the most worrisome was Washington’s failure to openly support its allies – the UAE and Saudi Arabia – in the aftermath of missile attacks by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen.

“Tony,” he continued, “you have to understand: They feel like they’ve been abandoned by their ally. I’m offering a solution. Come, we’ll sit quietly, without interference, without our staffs, and you look them in the eye and tell them that you’re not withdrawing from the Middle East.”

Lapid understood how delicate the situation was. He had also cultivated warm personal relationships with his peers, communicating often about state and personal matters on the Signal app. They had developed a friendly rapport in a short time, which helped Lapid to understand and advocate on their behalf.

“Their fear began developing the moment the Biden Administration announced that the most important subjects to the new president were China and climate change,” a senior Israeli diplomatic source told me. “Early in the year there were missile attacks on Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Americans took 23 days to pick up the phone.”

MBS (Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman) and MBZ were quick to respond to the cold shoulder from Washington with a chillier one of their own. When the war in Ukraine began in late February, and the global energy shock began to spread, the two Middle Eastern leaders refused to take calls from President Biden. He wanted them to increase the flow of oil and gas into the global market to ease the shock to the US economy.

Lapid and Bennett spotted the crisis. And the opportunity.

III. The Negev Summit

Still sensing some hesitation, Lapid gently pushed his major benefactor, indicating how he, Lapid, totally understood the dilemma: “I get that this is all a big misunderstanding, and I get what you’re telling me. It’s all good. But come and say it to them. It’s a win-win.”

Talk about organizing a shotgun wedding.

Within three days the idea had become a major summit.

IV. The First Night at Kedma

The atmosphere was reportedly congenial, pleasant and fun.

Read Attila Somfalvi's one-on-one interview with MK Mansour Abbas

V. The Morning After

The next morning, as Israelis were mourning the victims of the Hadera attack, the Negev Summit continued.

Unexpectedly, an official in Blinken's entourage suggested forming a working group that would address the Palestinian issue. Lapid stiffened.

“What do you want from my life?” he scolded, half-jokingly. “There will be no such group. You don’t understand the kind of coalition I’ve got in Israel?” That was the end of that.

In spite of the success of the Negev Summit, the Palestinians aren’t going anywhere. If anything, the Abraham Accords only increased the level of frustration the Palestinians feel from the increasing global disinterest in their plight and their demands.

Israel’s diplomatic successes have not had any effect on the unresolved issues between Israel and the Palestinians, nor on the sense of neglect that many Israeli Arabs may feel.

Prof. Youssef Masharawi, chairman of the steering committee to integrate Arab students at Tel Aviv University, challenges what he sees as an Israeli approach that deliberately ignores the Palestinian issue, and warns about the fire that is smoldering beneath the surface.

“In the Arab community there’s a sense of ‘trust-but-verify’ vis-à-vis the Abraham Accords,” he says. “They’re always trying to put the real story, the harsh, human story of the occupation, to the side. And it blows up every year before Ramadan. It’s been a whole year of suffering and hopelessness, of people getting shot to death in the street. Why do they think they can sweep it under the rug and hide it?”

Kobi Michael, an expert on the Palestinians and a senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University, has studied the deterioration of the diplomatic status of the Palestinians in recent years.

Palestinian leadership, he notes, has adhered rigidly to its refusal to acknowledge any normalization of relations between Israel and the Arab world, and sees such developments as a threat to Palestinian national and strategic interests.

Arab leaders, however, had made their own calculation: They see Israel as a critically important ally. And the obstructionist Palestinian approach has worn out everyone.

“Everyone understands,” a senior diplomatic source explained to me recently, “that there’s nothing to do. The Palestinians are divided. Half went with terror and the other half with corruption. With whom do you negotiate?”

VII. Shifting Sands

The Israeli prime minister cannot ignore the Palestinian issue, but Naftali Bennett made clear from day one to his coalition partners that he would maintain the status quo.

Bennett resolved to rebuff any diplomatic contact with Palestinian Authority Chairman Mahmoud Abbas. His view was that nothing good can come of such an initiative because there is no one to talk to and nothing to talk about. And Hamas, clearly, is a non-starter.

Bennett later learned, to his surprise, the degree to which Arab states in the region had also given up on the Palestinians.

“Everyone understands,” a senior diplomatic source explained to me recently, “that there’s nothing to do. The Palestinians are divided. Half went with terror and the other half with corruption. With whom do you negotiate?”

But in Israel, it is also understood that for all the good that is happening, the momentum can only continue for only as long as there is calm on the ground.

The violence at Al-Aqsa Mosque during Ramadan and the spike in terror attacks in recent months could well change the equation and give rise to a sense of instability – both inside Israel and in regional relations.

“This whole summit miracle took place when there was almost complete quiet on the security front,” a senior Israeli source familiar with regional diplomatic developments told me. “The Palestinian issue wasn’t bubbling over. Until now, everyone in the region is very happy with how we are handling the Palestinians, because they understand there’s nothing that can be done with them. But everyone also demands that the economic situation of the Palestinians be improved. This government has done a lot in that area, but if the security tension keeps rising – it will become increasingly complicated.”

And then, there is the very volatile political situation in Israel. The Bennett-Lapid government is in serious peril, and its continuance depends significantly on security developments.

Everything can change in a flash.

At the Kedma Hotel on March 28, the participants were certain that there would be a second summit. The foreign ministers had only to agree on a location. The jocular exchange on this topic was ultimately resolved in Blinken’s favor: Las Vegas was the chosen venue.

Desert. High risk. Long odds. Who knows?

Then again, as Ben Gurion famously said (and no doubt he kept a watchful eye on the Kedma gathering): “Anyone who does not believe in miracles is not a realist.”

If you enjoyed reading this article, please consider becoming a Premium Subscriber to State of Tel Aviv.