3 Generals and a PM Debate Israeli Policy on Ukraine-Russia

Moav Vardi speaks to 3 of Israel's top generals, plus a former prime minister, about balancing values vs. interests with Ukraine-Russia policy

Note From the Editor, Vivian Bercovici:

I recall a meeting during my tenure as Canadian Ambassador to Israel when a senior defense official said, wryly: “There are lots of traffic jams these days in the skies over Syria.”

These were the early operational days of the “deconfliction mechanism” agreed upon between Israel and Russia. Moav Vardi puts this extraordinary period into context – when Israel and Russia coordinated aspects of the military activity in the Syrian skies – and why it may be imperilled.

Moav discusses the delicate status quo holding between Israel and Russia – for now – which may well have hit a rough patch. This superb analysis is a must-read to understand the complex relationship between Israel and Russia and the potential impact on the world.

And if you missed Moav's last piece on the mediation efforts of then-PM Naftali Bennett with Russia and Ukraine, you can read it here.

Enjoy.

On the morning of Thursday, March 3, exactly one week after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a small group of worshippers gathered at the Western Wall in the Old City of Jerusalem. As always, they recited prayers facing the immense 2000-year-old stones. But on this day, they were also draped in the Ukrainian flag.

That same afternoon, a number of foreign journalists were taken to a secret bunker in the Ukrainian capital to meet with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. In response to a question from Israeli reporter Itai Engel about his expectations of Israel, the President replied: “Today I saw a very interesting picture. Hassidic Jews, all kinds of people, standing at the Western Wall, wrapped in the yellow and blue Ukrainian flag.”

Zelensky, who was raised in a Jewish family, said to the journalists: “I was amazed.”

And then came a less congenial reply: “I spoke with Prime Minister Bennett, and I do not feel he is wrapped in our flag.” And, so, it seemed that the unvarnished response to Engel’s question was one of bitterness.

Kyiv was clearly displeased with Jerusalem’s conduct vis-à-vis Ukraine.

Zelensky had good reason to feel this way. For several weeks following the outbreak of the conflict between Moscow and Kyiv, the Israeli government refrained from publicly criticizing Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. Even as the magnitude of the intentional killing of civilians and the destruction of cities and civilian infrastructure by Russian soldiers became undeniable, Israel was critical of the horrific murders of civilians but stopped short of calling out Russia by name for being responsible.

In the international arena, too, while Israel voted in favor of the UN General Assembly’s decision to condemn Russia, it refrained from supporting a proposal for a similar denunciation led by the United States in the Security Council. This “double-speak” was noted, with displeasure, by President Zelensky.

“I spoke with Prime Minister Bennett, and I do not feel he is wrapped in our flag.” – Ukrainian Prime Minister, Volodymyr Zelensky

The Ukrainian government implored Israel to provide military aid and equipment to resist and repel Russian attack.

Yet it took two months for helmets and protective vests that Israel had agreed to supply to Ukraine at the outset of the war to arrive. Furthermore, the equipment was intended for use by civilian rescue forces, not the military.

Perhaps most galling to the Ukrainians, as well as many Israelis, was the refusal of the Israeli government to explicitly and publicly hold Russia responsible for the invasion of Ukraine; its failure to clearly identify the victim and the aggressor.

On Sunday, April 3, the world witnessed the shocking images streaming from the town of Bucha, near Kyiv, which revealed the results of the massacre perpetrated by Russian forces on Ukrainian civilians. Even still, Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid (who became prime minister last month), remained vague as to who was responsible for the savagery. “It is impossible to remain indifferent in the face of the horrific images from the city of Bucha near Kiev, from after the Russian army left,” he said, adding: “Intentionally harming a civilian population is a war crime and I strongly condemn it.”

Then-Prime Minister Naftali Bennett refrained from mentioning Russia by name, saying, “We are horrified by the scenes in Bucha and we strongly condemn them. The images are very difficult. The suffering of Ukrainian citizens is immense, and we are doing everything we can to help.”

This inelegant two-step by Israel did not go unnoticed by the Ukrainians. In fact, it enraged them.

Why, they must have asked themselves, does Israel insist on maintaining Russia's dignity? Why is it so afraid of offending Putin?

“The United States isn’t sending troops to Ukraine either and the Europeans have not yet completely ceased the purchasing of gas from Russia. Every country balances its own values with its fundamental interests.” – Maj. Gen. (Res.) Yaakov Amidror

I. January 31, 2013: A Turning Point in the Russia-Israel Relationship

To understand Israel's conduct vis-à-vis Russia in the current Ukraine crisis, we must go back nine and a half years. Late at night on January 31, 2013, fighter jets attacked a convoy of military vehicles in Syrian territory carrying advanced weapons – intended for Hezbollah – from the Damascus area toward Lebanon. It was the first attack carried out by Israel in Syria since the First Lebanon War in 1982, and it heralded a new mode of combat by the Israeli Air Force. Since that night, Israeli fighter aircraft have carried out hundreds of sorties in Syria as part of an ongoing effort to manage two strategic threats to Israel, both related to Iran's presence in Syria:

The first threat is Hezbollah's precision missile project. For more than a decade, this Lebanon-based Iranian proxy militia has been endeavoring to stockpile an arsenal of precision-guided missiles that can strike strategic targets within Israel. The components required to ensure maximum precision in the missiles originate in Iran and are then transported to Syria and Lebanon. On the last leg of the journey – to Lebanon – the IDF attacked the convoy of weapons and materiel and his been dedicated since that night to prevent the smuggling of these advanced components and weapons.

The second threat involves Iran's effort to establish a military front against Israel on the Golan Heights. Since 2014, the Iranians have been taking steps in southern Syria to develop a missile-launching system against Israel, in addition to attacking IDF forces deployed along the Israeli-Syrian border.

These two Iranian-backed operations in Syria were perceived then, and are today, as strategic threats to Israel, justifying the extensive air campaign to thwart these efforts. But within several years, there was a development that threatened to severely infringe on the IDF’s freedom of action in Syria.

II. Russian Interests in Syria

On September 9, 2015, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov announced that Russian military forces had deployed in Syria, ostensibly to fight “terrorists.” In actual fact they were there to ensure that Bashar al-Assad was able to hold on to power so that Syria would remain in Moscow’s sphere of influence. In practice, this meant that the Russians deployed advanced S-300 and S-400 anti-aircraft batteries into Syria – presenting a huge problem for Israeli fighter jets.

In Jerusalem, it was understood that these developments would prevent the IDF's continued freedom of action in Syrian skies, which was essential to deter the strategic threats. Just 12 days after Lavrov's announcement regarding the entry of Russian forces into Syria, Prime Minister Netanyahu landed in Moscow for an urgent meeting with President Putin. He was accompanied by the IDF chief of staff, the head of Military Intelligence, the national security adviser, and Minister Ze’ev Elkin (Ukraine-born who served as a translator). Journalists were not invited to join the trip, but, immediately following the two-and-a-half-hour meeting, Netanyahu spoke with Israeli diplomatic correspondents in a conference call from Moscow.

An agreement had been reached with Putin, Netanyahu confirmed, regarding the establishment of a “deconfliction mechanism.” This was a system of coordination between the Israeli Air Force and the Russian Air Force headquarters in Syria designed to prevent “misunderstandings” and unintended clashes between the IDF and Russian forces stationed in Syria.

“The Russians are giving us a free hand to take action against a threat that, for us, is a strategic threat with the potential to become an existential threat – the Iranian and Hezbollah forces in Syria. We need this freedom of action. To put it in danger would not be right.” – Maj. Gen. (Res.) Amos Gilead

Putin effectively agreed to look aside. This had the effect of ensuring that Israeli fighter jets could continue carrying out attacks on Iranian and Syrian targets on Syrian territory.

Was this only out of a sense of responsibility for Israel's security? Or also because the continued Israeli strikes served Putin's interest that Iran should not become too powerful a force in Syria? Whatever his motivation. Putin made a choice that was advantageous for Israel.

In the seven years since that meeting, Israel has made good use of the Russian decision. The IDF has attacked Iranian infrastructure and shipments of advanced weaponry in Syria which are intended for Hezbollah’s use. A military airport in Syria used by Iran has been struck repeatedly by Israel. It is estimated that to date, close to 700 Iranian, Syrian, and Hezbollah soldiers and operatives have been killed in these attacks.

III. Israel and Ukraine – The Generals Weigh In

When Russia invaded Ukraine on the morning of February 24 this year, the Israeli leadership decided to avoid any sharp criticism of Russia or condemnation of its attacks on Ukrainian civilians.

“Our interest is to be aligned with the West, led by the United States. The US is our ally, not Russia. Has Russia ever defended us in the UN Security Council and vetoed an anti-Israel decision? Only the United States has done that. Who is arming the Syrian forces, with weapons that eventually reach Hezbollah? It’s Russia.” – Maj. Gen. (Res.) Amos Yadlin

Israel further chose not to provide Ukraine with immediate military aid, not even helmets and protective vests. The pervasive fear among Israeli leadership was that if they did so that Putin may reverse his decision of September 2015, which many Israeli security officials regarded as being critically important to maintain.

For the Ukrainians and their allies in the West, this posturing by Israel has been perceived as being very problematic. In Israel, however, it has broad support.

“The United States isn’t sending troops to Ukraine either and the Europeans have not yet completely ceased the purchasing of gas from Russia. Every country balances its own values with its fundamental interests,” Maj. Gen. (Res.) Yaakov Amidror, who was Prime Minister Netanyahu's national security adviser from 2011 to 2013, said when we spoke recently.

“From a moral perspective, we think what Russia has done is wrong. But Israel has other interests, the most prominent and pressing of which is to avoid alienating Russia due to its deep involvement in Syria, where Israel has very, very clear interests – which, by the way, the world has ignored to this day.”

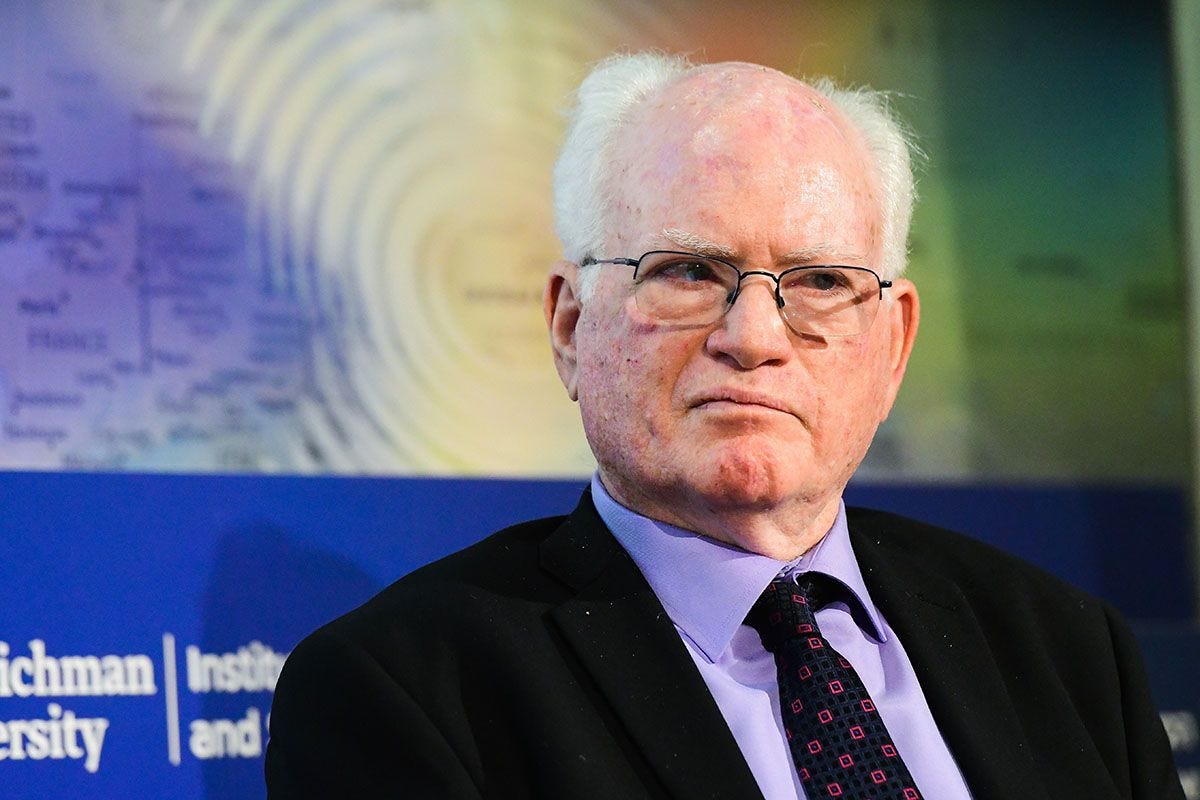

Maj. Gen. (Res.) Amos Gilead, who led the Defense Ministry's Political-Military Affairs Bureau for many years, adds another, practical explanation for Israel’s policy. “How great is our ability to influence the war in Ukraine by providing aid to Kyiv? It’s almost nonexistent,” says Gilead, who now heads the Institute for Policy and Strategy at Reichman University in Herzliya.

“The Russians are giving us a free hand to take action against a threat that, for us, is a strategic threat with the potential to become an existential threat – the Iranian and Hezbollah forces in Syria. We need this freedom of action. To put it in danger would not be right.”

But other former military leaders have expressed different opinions on this issue, among them of Maj. Gen. (Res.) Amos Yadlin, who was the head of Military Intelligence when the IDF destroyed the nuclear reactor in Syria in 2007. “Our interest is to be aligned with the West, led by the United States. The US is our ally, not Russia. Has Russia ever defended us in the UN Security Council and vetoed an anti-Israel decision? Only the United States has done that. Who is arming the Syrian forces, with weapons that eventually reach Hezbollah? It’s Russia.”

Yadlin, who until last year headed the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) is currently a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School. When we spoke about this issue his anger came through, clearly.

Yadlin questions the logic behind Israel’s current policy toward Russia. “The Americans are saying to themselves, ‘These damn Israelis – we give them money, we protect them in the Security Council, we give them F-35s, and now they tell us they need to be considerate of Russia?’ We don’t expect that from our Israeli allies. It’s befitting of a country like Iran. It is not befitting of Israel. We have values that are also interests. We can’t remain silent when one country invades another, because if another country tries to invade us, we want the world to come to our aid.”

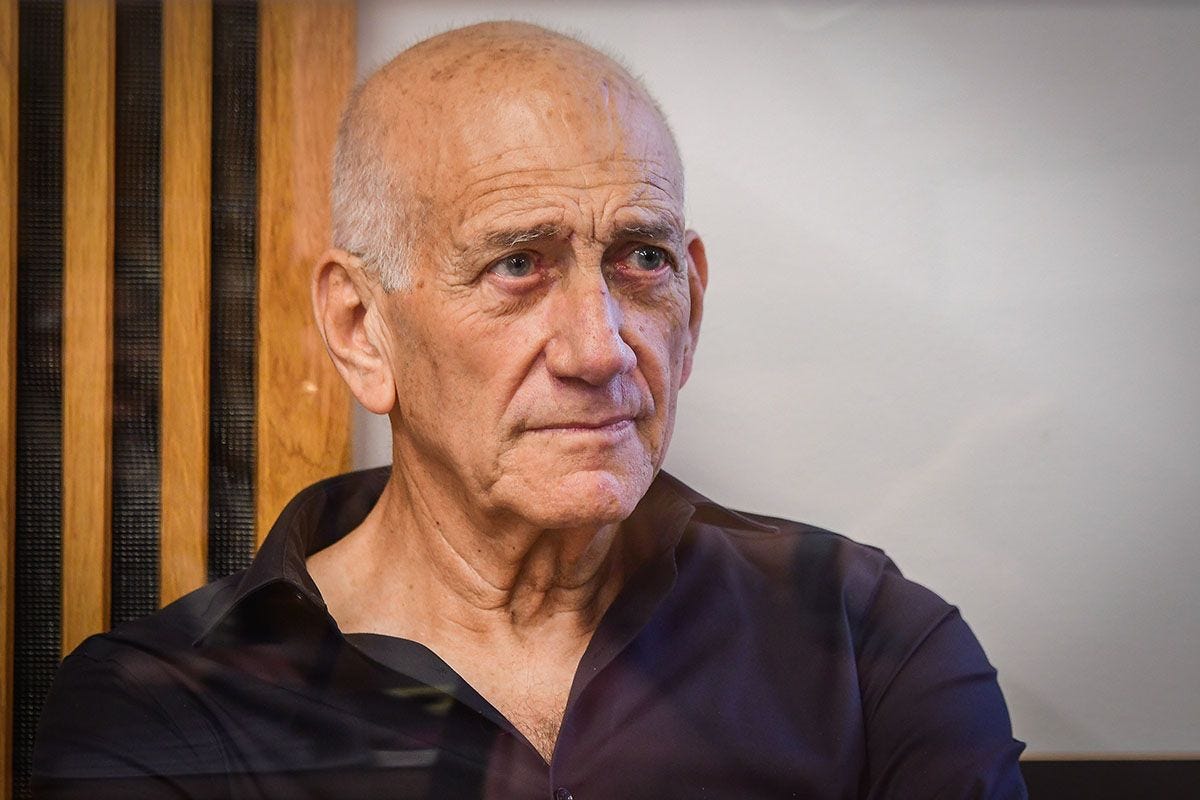

Equally fiery and critical of the Israeli government on its handling of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert.

“We should have taken a much sharper and clearer position against the Russian invasion from the outset. We should have called Russia by its name and said ‘This is unacceptable. We condemn it in the strongest possible terms.’

And no consideration of temporary, operational convenience on our northern border should affect this.”

The question, of course, is what price Israel might pay if it were to adopt a policy critical of Russia, as Olmert and Yadlin advocate. To some extent, this has already been put to the test.

IV. ISRAEL TALKS TOUGH AND RUSSIA REACTS

Two days after the pictures of the massacre in Bucha emerged, Foreign Minister Lapid decided to take off the diplomatic gloves and began speaking out against Russia in clear terms. He named Russia as being responsible for the massacre, and in early April, following the UN General Assembly's decision to suspend Russia from the Human Rights Council, Lapid stated that Israel supported the suspension due to Russia's unjustified invasion of Ukraine and the killing of innocent civilians by Russian forces.

“We should have taken a much sharper and clearer position against the Russian invasion from the outset. We should have called Russia by its name and said ‘This is unacceptable. We condemn it in the strongest possible terms.’" – Former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert

The Russian reaction was harsh. Israel's Ambassador to Russia was summoned for a dressing down at the Foreign Ministry in Moscow. An unusually strong statement was also issued, lashing out at Lapid. Russia accused Lapid of criticizing them in order to divert the attention of the international community from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Most significantly, on Friday May 13, 2022 a very worrisome “interaction” occurred. On that evening. Israeli jets launched an attack against facilities at a precision missile development site in western Syria.

After the strike, an S-300 anti-aircraft missile battery stationed nearby launched numerous missiles in the general direction of the Israeli aircraft. The battery’s radar did not lock onto the planes, meaning that the missiles fired did not pose a real threat to the aircraft. But it may well have been a warning shot across the bow; a sign that something in Moscow had changed. Although the batteries were in the possession of the Syrian army, they are operated by Russian officers.

This is precisely the sort of entanglement that the “deconfliction mechanism” agreed upon in September 2015, was meant to avoid.

Were the Russians changing the rules?

Ehud Olmert, who as prime minister made the decision to attack the Syrian nuclear reactor in 2007, refuses to let this concern him. “There is indeed a chance that one day, the Russians will decide to fire the S-300 or S-400 towards our planes,” he says, “but they know we know how to deal with these batteries, and then everyone would know that Russia was launching missiles but not hitting anything, and that is not something they want at the moment. And it would be a declaration of war against us by Russia. So the question is not just ‘Are you willing to poke the Russian bear?’ The question is also, ‘Does the Russian bear currently have an interest in entering into a violent confrontation with Israel while he is engaged in a war elsewhere and is not really succeeding there.”

Maj. Gen. Amidror thinks otherwise. “At the end of the day it’s a question of probabilities. There is no such thing as zero risk. No one knows exactly what the risk is. Those who say that Russia has no interest and may not have the ability to harm us in Syria right now may be right. But let's say there's a 20 percent chance that they're wrong. Would you be willing to send our planes on these missions when there's a 20 percent chance they’ll be hit? And for what?”

V. ISRAEL ON THE KNIFE EDGE: CAN VALUES AND INTERESTS BE RECONCILED?

This may, then, seem to be a dilemma in the field of risk management. But it would appear that, more than anything, it is fundamentally related to a worldview and the question of how Israel perceives itself. And it is on this point that the Israelis disagree. “Even if I erred in my assessment of the the Russians’ intentions and capabilities, the price to pay is a reasonable one,” says Maj. Gen. Yadlin. “Israel belongs to the Western, democratic camp, and when a democratic country headed by a president who also happens to be a Jew is attacked in a brutal and unrestrained manner by a neighboring state who is committing war crimes, I think Israel should support that attacked country. Because tomorrow, it will happen to Latvia or Poland or another country, and we need to be in the right camp.”

Amidror, however, has allegations against this alliance of interests to which Israel seems to want to belong. “The hypocritical world has not done, and is not doing, anything in the face of the Iranian threat. All those in the international community who are now preaching to us about our position on Ukraine – what are they doing to stop Iran's threat to the State of Israel?”

But are there not values that a state should adhere to, lest it risk losing its identity? “Of course there are values,” replies Maj. Gen. Gilead. “But should Iran decide tomorrow to attack Israel using all its capabilities in the region, including firing missiles from Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen – and keeping in mind that one day it may also have nuclear weapons – do you think someone will come to our aid? No one will come. No one. We need to be able to defend ourselves, and without the freedom of action we now have in Syria, we are simply endangering the survival of the state.”

Olmert looks at the same situation and draws the opposite conclusion. “The State of Israel needs to decide what its ideological core is, what is at the essence of its identity,” says the former prime minister. “Is it a state whose main goal is to simply get by from a practical standpoint? Or is it a country that has a fundamental moral commitment to certain principles that underlie its existence?”

The State of Israel has been trying to walk a tightrope in dealing with the war in Ukraine. But this story has “legs”, as we say in the news business. The status quo between Israel and Russia is very fluid.

The main question is how Israel’s current policy towards Russia and Ukraine will affect its global standing going forward and its legitimacy in the eyes of the international community. Values do not have to conflict with interests. Sometimes, values are the interest itself. If the world judges Israel in the future as a state that, due to its stance on the Ukraine crisis, effectively removed itself from the club of Western democracies, that group may change its policy toward Israel. And such a dynamic is liable to harm Israel's national security interests no less than a temporary decrease in the IDF's freedom of action over Syrian skies.

This article is available to read for paid subscribers only. Thank you for being a member of the State of Tel Aviv community.